By Jordy Dakin

Jordy Dakin: The concepts of myth and mythologizing as you explore them in your essay extend to everything from sea monsters, relatives passed on, and ice cream. The connections are seemingly tenuous at first, but end up fitting together quite nicely and providing the essay with a helter-skelter, yet still logical structure. Can you tell us a bit about how you developed the connections and about your process of structuring the essay?

Matthew Gavin Frank: So when I first saw the carcass of the giant squid in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, it did not strike me as all that obsession-worthy. It was desiccated and crusty. But when I saw the photograph on the wall above it—the one (as I learned from the 3-line caption) taken by Reverend Moses Harvey in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1874; the first-ever photograph of the giant squid; the image that rescued the animal from the realm of mythology and finally proved its existence; the one in which its carcass is draped over Harvey’s bathtub curtain rod in order to showcase its full size—that did it. I wanted to know what the giant squid, and our engagements of, and reaction to it could tell us about ourselves. The poet Alberto Rios writes of "turning away from the explosion," addressing the duty of writers to turn their backs on the subjects that are primarily inflaming them, and recording, then, what they see in the other direction. The theory is that these seemingly dissimilar things, glimpsed only when turning the back on the main subject, have something to say about that main subject. At various intervals, I turned my back on the giant squid and found these ancillary subjects (which turned out to be ice cream, my long-dead saxophonist grandfather, various cultural expressions of pain, and—in an early draft—puppets and puppet parts) that began to haunt the narrative. These things had something to say about the squid, and the squid, and what it means, changed due to its proximity to these things. Eventually, I hit a wall in the writing process, and I lit out for Newfoundland in order to shake something loose, immerse myself in what the filmmaker Werner Herzog likes to call “the voodoo of place.” I stalked the current resident of the Harvey home when I was there. I needed to see that bathroom in which a giant squid once hung. During the writing process I spent most of my time trying to map my own ecstasy (in the face of uncovering and shuffling through all of this awesome research) onto Harvey’s assured ecstasy in the face of that fateful squid, and all of the lovely and awful ways that it changed his life.

JD: When I purchased the book, I found it in the “Nature” section at Barnes & Noble. And yet this is obviously far more than just nature writing—you play around with history, biography, biology, and personal essay, among other forms. The fact that it can’t be pinned down to one precise genre seems to transform it into a myth of its own, a monster that can’t be known. How do you see genre, or the form of your essay, functioning in relation to its content?

MGF: I love that. Hell. Thank you. Honestly, I don't know what nature writing even means, so I don't know if Ghost is far more or far less, or if amounts and percentages should even come into play. I guess since there's an ocean in it and a squid in it, the book engages some sort of nature. I think a tree might even make an appearance about a third of the way in. It seems that the current trend (which is not a bad thing, because it is inevitable and energetic), is to disavow easy labels for what we do. Nonfiction clearly means very little, and creative nonfiction is silly, and literary nonfiction is silly, and narrative nonfiction is silly, and lyric essay may be played-out, and just plain essay has been fucked over by the academy, and let's face it, bookstores want to sell books. I know some essayists now who tell me that they're creating artifacts. I don't yet know whether to love or hate that. Anyhow, regarding the form of Ghost: Structurally, these ancillary subjects I mentioned began to draw a chalk outline around the squid, and the trick was finding the right blend of chalk to evoke the body. Or maybe, structurally, the process was more akin to the overlaying of those onion-skins—one atop another—in those architectural diagrams. If you have the right amount of onion-skins, you can envision the entire anatomy of the building—all of these seemingly dissimilar parts: metal and wood and cement—coming together to make one thing. And then you can ornament it—put in couches and stuff, a fireplace. And then you can do stuff in it—eat and fuck and sleep and live. Invite friends over. Too many onion-skins, and the building collapses.

JD: I’m fascinated by Joan Didion’s assertion that “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” as well as Dr. Clyde Roper’s, that “people must have their monsters.” Why do you think this is? And more importantly, what are the consequences when we “kill our monsters,” expose them as either fact or fiction, photograph our myths?

MGF: Clearly, we're a species that needs to girdle our world in order to make it manageable, digestible, and we do that girdling, oftentimes, with narrative. We do it also via the ways in which we frame scientific inquiry, construct a work of literature, paint a painting, pick and choose aspects of a religion and then dress ourselves in said aspects. Sometimes, I think it's the duty of art to hew through the chaos, the white noise, and to laser focus on the holiness of one or two small things suspended within it. Sometimes, though, art needs to muddy our attempts to wedge manageability into the crevices of the world. Sometimes, art needs to call out our narratives (and their desire to simplify the world for us) as illusory. To call attention to the mess. To agitate rather than to confirm. In "killing our monsters" we engage in a violent act (actually or rhetorically) and allow ourselves the power to kill not only our own inventions and projections, (which, depending on the context, can be good for us, or bad for us), but also the physical manifestations of said projections—like, for instance, the giant squid. First, we claimed ownership of it via mythology—it became a tool in our stories; stories that served us, of course, and not the squid. Then, we further lorded our power over it by taking its photograph, which allowed us to discard its previous narrative usefulness, and to invent new ways in which we can use it—in art, literature, religion, and now, the dissection table. If Roper's right, and we must have our monsters, then the consequence of killing our monsters is that we will soon busy ourselves with reducing yet another intricate nuanced thing with which we share this world to a monster; and we will do this at our convenience.

JD: They way you’ve written the real-life Moses Harvey relies heavily on speculation, invention, and “professional leeway”—much like, as you’ve pointed out, the reconstruction of a dinosaur skeleton, or a Neanderthal diorama in a museum—and your essay treats fact and fiction as equals, both of them legitimate and effective devices in carrying the essay forward. What role do you see invention or fictionalization playing in your essay?

MGF: I see invention and fictionalization—just as I see archival and observational research—as tools required for building truth. It's the essay's duty, after all, to interrogate facts, to test their parameters. To see what they're made of. How much scratching can a fact take before it begins to bleed, or to leak out some holy inner stuff? What happens when we strip a fact of its swagger and bravado? When we wedge one fact up against a seemingly dissimilar fact and gawk from the shadows to see how they react, collide, repel, couple, bump-and-grind, kiss each other goodbye? Is there magnetism? Electricity? Aversion? Does one fact wilt and become something else? Mere image? Fiction, maybe? Archival research dictates that Moses Harvey died in at least two ways—deliberate suicide and accidental fall. Which was it? Both narratives thrive in various obituaries printed by reputable newspapers. Fact and narrative are ever-entwined, and the rendering of fact is ever subject to human flight-of-fancy—to boredom or excitement, or agenda; to getting caught-up. Facts and speculation based on said facts depend on each other. How can we get to the heart of one without the other?

JD: I’m dying to know your favorite flavor of ice cream.

MGF: As a savory first-course: chicken liver ice cream with crispy pancetta, supremed blood orange, maple-caramelized onion, toasted hazelnuts, and Gewurztraminer gelee.

Jordy Dakin is a third year Creative Writing student focusing on fiction. He is an avid collector of hometowns, which include Santa Rosa, California; Grandview, Washington; West Monroe, Louisiana; Ouray, Colorado; Oakhurst, California; Branson, Missouri; Bonney Lake, Washington; and now Fresno. He is currently at work on his first novel.

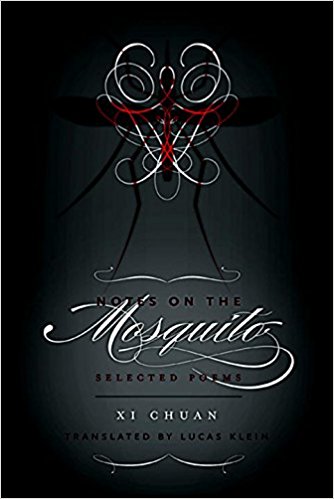

Artwork is by Robert Amador, a drawer / painter / muralist / toy-maker / gardener, living and working in the Central San Joaquin Valley of California. His belongings have layers of dog hair, and his lungs are coated in graphite.