These grape-sized blobs of I-don’t-know-and-I-didn’t-ask are what kept my sinuses from filling with air. They also kept them from flushing out all the horrible mucus. Thus: infection, pain, poor breathing, infection, gunk, embarrassment, infection, more pain, a box of Kleenex on every flat surface of my home, burning, swelling, infection, pain. Repeat cycle once each month.

Read MoreThe Exhibit Will Be So Marked (Treemix 12” Remix with Fade-Out) by Ander Monson

A couple of years ago, I asked friends and family to make me a mix CD for my birthday, hoping to get 33 mix CDs, one per year I’d lived. I got 59, including some, pleasingly, from strangers. Somewhat predictably, though not unpleasantly, there were a number of Jesus-Year-themed mixes, though fewer Jesus-themed songs. I also put out the call to friends to pass it to anyone they thought might be interested in sending a mix CD. I made it a project to listen actively to each of these mix CDs and to respond by annotating, riffing on, and responding to the selections, and sending a note with my response to the mix-maker, or I suppose we should call her an arranger, since therein is the art of the mix.

Read MorePanel Discussions: Look! Up in the Sky! By William Bradley

The recent PBS documentary Superheroes: A Never-Ending Battle showed footage of a young Christopher Reeve talking about Superman’s continued relevance, as part of the 1980 television documentary The Making of Superman: The Movie. “We all know that the Man of Steel could leap over tall buildings, but the question is, could he leap over the generation gaps since the early Jerry Siegel / Joe Schuster days? We wanted to know if the man from the innocent thirties could survive in the post-Watergate seventies.” Then, looking directly into the camera, Reeve told the viewers, “Well, thanks to all of you, he’s doing just fine.”

Read MoreJustin Hocking on surfing, the White Death, Melville's ghost, and his new memoir, The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld which was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great Writers selection, and of which he says, "I took my cues from Moby-Dick—a sprawling, polyphonic, multivalent work that blends the personal with the political and the metaphysical."

A Normal Interview With Justin Hocking

Rusty Birdwell: How did you decide on the book’s structure? The titled sections range from one paragraph to several pages (one of my favorite sections being 'Samsara')—how do the short and long sections, and white space, serve the book?

Justin Hocking: Wonderworld revolves largely around my longtime preoccupation with the life of Herman Melville and his novel Moby-Dick. Writing about a classic work definitely involved some risks, and one thing I wanted to avoid was any sort of literary ventriloquism. On the other hand, I did allow myself to draw inspiration from what I found in Moby-Dick's unconventional structure, which is that all things are admissible within the bounds of a single work: short sections, long sections, fiction and nonfiction, stagecraft, slapstick humor, reportage, meditations, environmental writing, literary criticism, etc. This freed me up to digress and meander and experiment with form. I organized one of the longer, crux sections, "The City Swell," as a series of surf reports. Within the shorter sections, I was striving for a kind of economy and compression of language that we find in work by poet-memoirists like Nick Flynn. Flynn and others allow for white space and gaps in their poetry and nonfiction, in a way that trusts the reader to make their own connections, without leaning too heavily on conventional, linear narrative. Most poetry collections rely on a slow accretion of resonant images, themes and language, and that was definitely part of the effect I was hoping for in the memoir.

RB: The best books strive toward the universal and the personal; this book steps seamlessly between the two. In some ways this could occur without the larger tale of the American spirit’s dark journey. Why was it so important for you to include the political, industrial, American-spirit landscape in the book?

JH: In the narrative I took some deep dives into my own messy emotional territory, but I also tried to repeatedly bust out of the traditional memoir format. I needed to get the reader (and myself) out of my head quite a bit, to hopefully avoid the sense of claustrophobia that can sometimes plague a memoir or any first person narrative. So I did quite a lot of outward expansion and weaving in news of the wider world, in hope of rendering the deeply personal material more balanced and bearable for the reader. I also wanted to risk some of the grand, sweeping historical/political/philosophical gestures that Melville did, especially since much of the story took place at the height of the war in Iraq. I got fascinated, for instance, with the history of surfing, and how it ties in with the history of American colonialism in Hawaii and elsewhere. And the more I read Moby-Dick, the more I began noticing parallels between the historic whaling industry (which was all about whale oil), and our contemporary petroleum industry. Another chapter deals with the environmental repercussions of the this industry, specifically a massive oil spill that took place in North Brooklyn in the mid 20th Century. It was a much larger, more insidious spill than the Exxon Valdez disaster, but most people have never heard about it, even though it happened in a city populated by eight million or more people. These are all important issues to me, and again, I took my cues from Moby-Dick—a sprawling, polyphonic, multivalent work that blends the personal with the political and the metaphysical.

RB: Melville eventually becomes a physically present character, following you around, sort of torturing you or communing with you in your own dark period. From the first hint of his almost-presence on page 61 to his finding you in bed or in a bathroom stall, how did this come about in the book?

JH: I'm a big fan of literary writers who delve into the surreal—George Saunders, Karen Russell, and Borges all come to mind. I wanted to see if I could pull it off in nonfiction, as a way to lend some narrative immediacy to this sense I had, while in New York, of feeling both haunted and inspired by Melville. It was another somewhat risky move that I worried might come off as maudlin. There were a couple moments, though, where I utilized Melville's specter as a kind of stand-in or body double for some of my darkest emotions, in a way that I hope actually helped me avoid melodrama.

RB: Could you talk a bit about the L train becoming sentient and somewhat omniscient? It tells a random woman on the subway a lot about you, about some pretty deep moments of internal turmoil for you. It’s the train that really introduces us to you starting to lose your shit. Did this have something to do with the book needing narrative distance at that point?

JH: It was absolutely about narrative distance. Revealing my struggles with anxiety and phobias wasn't easy; the shift from first to third person allowed me, as the writer, a little distance and perspective. I also hoped it would give the reader some respectful breathing room while I explicated my personal problems. Utilizing the L Train voice was also another way to experiment with the surreal, and to channel some of the of chaos and noise and weird allure of New York City life.

RB: You give us plenty of examples of other writers and artists who have suffered the White Death. This is the form of obsession the book uses as a lens for all sorts of ailments of spirit and addiction. Do you consider the White Death beneficial if it runs its course without killing the carrier?

JH: During my research, I was surprised to discover how many other writers and artists struggle with bouts of the White Death, which I define as an all-consuming obsession with Moby-Dick. The visual artist Frank Stella spent twelve years creating fifteen hundred abstract paintings and sculptures, each inspired by Moby-Dick; he claims the obsession nearly destroyed him. More recently, illustrator Matt Kish made one drawing a day, every day, for all 552 pages of his version of Moby-Dick. The writer Sena Jeter Naslund grew obsessed with Moby-Dick at age thirteen; she later wrote the 666 page novel Ahab's Wife. So yes, I think the White Death is more of a creative catalyst than a disease. Probably my favorite example is the playwright Tony Kushner, who claims Moby-Dick as the single most important influence on his work, and that he learned from Melville that it's better to risk total catastrophe than to play it safe as an artist.

RB: Much of the book deals with obsession and addiction—from emotional need and drug addiction to American’s continuing petroleum binge—are these in some way, necessary first steps in a Nekyian journey?

JH: I first encountered the term "Nekyia" in a book called Melville's Moby-Dick: An American Nekyia by the Jungian analyst and critic Edward Edinger. Edinger defines the Nekyia as a kind of "night sea journey" through despair and meaninglessness that we all embark on during our development as individuals and a society; he interprets Moby-Dick as a quintessentially American version of the Nekyia. The word Nekyia derives from the eleventh book of The Odyssey, wherein Odysseus descends to the underworld to commune with the dead. These archetypal voyages often begin with a literal or metaphorical descent, and the potent darkness we encounter there is often a necessary first step in the circuitous journey back home.

RB: Overall the book seems to beg us to see dark times as first passages toward journeys that involve revelation and self-awareness. Reaching something good also seems to come out of a sense of community—deliverance through interdependence (not codependence) seems like a big theme of the book as well. Is this the best track for the deepest problems in the realms of both the personal and the social?

JH: When thinking about or discussing Moby-Dick, most people focus on the narrative of Ahab's revenge against the White Whale. That's certainly a huge part of the story, but it brings up the question of ownership. To whom does the story really belong? In my opinion, the narrative of Moby-Dick belongs principally to the narrator, Ishmael. And his is a story not of revenge, but of interconnection and survival. So I'm much more interested in the book as a survival story. Not just our survival as individuals, but also survival in a larger sense, as we continue to encounter massive, late Holocene extinction of species. And especially as we enter this new, Anthropocene era, where the entire planet's survival will require that we challenge the notions of humankind's disconnection from and dominion over the natural world.

RB: Surfing definitely brought you closer to Melville’s understanding of the ocean—can you talk a little about the process, about how surfing changed your understanding of the ocean and of your internal self?

JH: I grew up in Colorado and California, so the lack of true open space in New York was definitely a shock to the system. The one true open space I found was the coast, at spots like Rockaway Beach, in Queens. As I grew increasingly disillusioned with city life, I gravitated toward Rockaway. Surfing became my solace during an otherwise difficult time. The combination of salt water and physical exertion leaves you feeling scoured out and completely at ease in the world. Melville literally spent years at sea, whereas I only dipped my toes in, so to speak. So I don't think I came anywhere close to his level of understanding of how the ocean can connect us with a sense of primal universality. Melville wasn't a starry-eyed Transcendentalist, though; he was keenly aware of nature's tremendous dark side. As things got more emotionally precarious for me, I started taking some unnecessary risks in the ocean, and eventually had my own modest yet terrifying experience of what Melville called the "sledgehammering seas."

RB: Any trepidation about calling the book a memoir? In recent years memoirs have gotten a bad rap. Does this categorization worry you at all?

JH: Not really, because all my favorite works in recent years are memoirs: Another Bullshit Night in Suck City by Nick Flynn, Lit by Mary Karr, The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch, just to name a few. These books all push hard against the traditional boundaries of memoir. They take big formal and emotional risks. I challenge anyone to read Another Bullshit Night or Chronology of Water and then try to tell me there's something inherently "wrong" or "bad" about the genre. Memoir has gotten a bad rap because every time some asshole like James Frey fabricates an entire narrative, people use it as an excuse to bash the genre as "failed journalism." But memoir is not journalism. To me, it's one of the most elastic and dynamic literary forms out there, especially when handled by writers who stretch its limits and expand our notions of what it can accomplish, both as an art form and as a vessel for deep communion between writers and readers.

Justin Hocking’s memoir, The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld, was published by Graywolf Press in early 2014 and was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection. Hocking is a recipient of the Willamette Writers' 2014 Humanitarian Award for his work in publishing, writing, and teaching. His nonfiction and fiction have appeared in The Rumpus, Orion Magazine, Portland Review, The Portland Noir Anthology, Poets and Writers Magazine, Swap/Concessions, Rattapallax, and elsewhere.

Relationships built strong through the bonds of love and music, inspiration instilled from travel, and fragile beauty only found through loss are just a few of the many rooms inside the gallery of Jericho Parms' Lost Wax (University of Georgia Press). It is an exquisite exploration into her journey from childhood to adulthood as a woman of color living in the United States. Jericho's writings have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, noted in Best American Essays, and anthologized in Brief Encounters: A Collection of Contemporary Nonfiction. Her essay "Still Life with Chair" was previously published in The Normal School.

A Normal Interview with Jericho Parms

By Elizabeth Bolanos

Elizabeth Bolanos: Lost Wax felt to me like such a remarkably humble yet perfect title for your book. You’re a writer, a traveler, a professor, and assistant director of an MFA program. I sensed that as a child, you may have imagined yourself exploring all these areas. How did all these elements come together for you?

Jericho Parms: I had many imaginations as a child that related to traveling and exploring a world that I knew early on was much larger than my own experience of it. I often credit that to my parents who nurtured curiosity and a sense of exploration when I was young. Art and writing were key components of that experience, but it was really when I was a bit older, and began to write and travel on my own when I was in college that those interests began to coalesce, first through a budding passion for journalism, then during the years I worked in an art museum. When I stumbled on the essay as a form, it allowed all of those interests to come together.

EB: You’ve visited so many places, from Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Guatemala, to all over the United States. What’s your favorite travel destination and why?

JP: Picking favorites is such a challenge. Ireland holds a special place for me, and is one of the more strikingly beautiful places I’ve been in recent years. I admire, too, the palpable sense of history and deep respect for literary culture in Ireland. Spain is the place I have most returned to, for many reasons, not least of which because it was one of the first countries I explored on my own. Spain has always renewed my sense of independence and exploration, my love of color and texture, and being there inspires me to slow down, to take things in. But there are, of course, so many remarkable places I still hope to visit.

EB: In Lost Wax, you talk about color, quoting painter Hans Hofmann’s understanding of it and giving us your own examples, such as red being the color of love and lunacy. You also mention a friend who said different kinds of reds, like burgundy, mean different things. If you could describe yourself using only colors, what would they be? Or would describing yourself using only colors even be possible?

JP: I like to imagine we are all living mood rings, constantly changing our colors depending on the day, the hour, the weather, our company or solitude. In that sense, I don’t know that I could describe myself using color with any certainty. Talk long enough about color and I think we inevitably fall into the realm of synesthesia, or at the very least, metaphor. The spectrum of colors we assign to our own identities and those of others—and the language of those colors—is a topic I’ve been exploring through writing lately. Where do our concepts of whiteness and blackness begin and end? What does it mean to be a brown face in a predominantly white space? How does our use of language when applied to identity contribute to or bridge the human divides we continuously find ourselves facing?

To circle back to Hans Hofmann, “It is not the form that dictates the color but the color that brings out the form.” The essay “A Chapter on Red,” in which Hofmann’s line serves as an epigraph, was an attempt to explore and reveal the meditative quality and associative potential of color to both reflect and expose experience. And yet, any writer would have approached an essay on red differently. Color is a series of perceptions, after all. We all see and conceptualize color differently, which means that in the end, color can both illuminate and blind us to the reality of our shared human condition.

EB: Your book also made me think about memory. There’s a part where you mention the memory of a fruit stand where you and a boy you once loved would sit down and eat peaches after seeing a movie. He would talk about the fruit trees in Romania. You said when you were informed by a friend that the fruit stand was gone, the memories of those times with him were all you thought about that day. Why did that moment and that memory stick with you?

JP: I find the workings of memory and our human senses endlessly inspiring, and often I try to mine memory for small moments or details that, when we allow ourselves to linger and meditate on them, can serve as portals to something larger or offer an unexpected foray into meaning. The essay “Origins” is in many way an homage to the senses and the ways in which the sensory quality of language can unearth experience. We often talk about the “occasion” of an essay—the reason for the writer writing at the present moment. I think that can occur on both a large and small scale within an essay as well. News of the fruit stand being gone served as one of many “occasions” in the essay to think back on certain moments (in this case, sharing fruit with a friend). But inclusion of those small memories are less about the experience itself (however sweet it may have been) and more about how it allows me to linger in the sense of nostalgia and indulgence that each sensory detail can convey.

EB: Another part of your memories that stuck with me were the parts about your childhood, before your parents’ divorce, when you talked about the relationship you had with your father when he introduced the world of music to you. One example in the book was where you would practice My Fair Lady together. What’s your fondest music memory with your father?

JP: The essay “The B Side” is written in three parts, and explores my relationship to my father in various stages from childhood to early adulthood through the lens of music—both reflections on the moments we shared when I was young, and the role music came to play in my life as I grew older. The recording sessions I describe in the essay definitely represent some of the fondest memories I have. However, as I alluded to in the piece, I am deeply grateful that those moments were recorded. At various moments I have found myself returning to them and this carries its own satisfaction and wonder, like rereading a book you’ve always loved after time has passed and extracting new details and meaning from its passages.

EB: “Immortal Wound” is the last essay in the book and it’s my favorite. The piece involves the dead luna moth you noticed as you were walking past a bar. You bring up a beautiful point about humans’ similarity to insects: how we feed on our findings, spin strangeness, glide through, behave nocturnally and are drawn to things the way moths are drawn to light. Was that moment inspirational to you, for more travel and exploration, or the opposite?

JP: “Immortal Wound” is an essay I hold dear because it preserves an experience that, while seemingly simple, felt laced with potential metaphor and meaning at the time and therefore conjured a sense of responsibility to describe, to record, to take notice, to pay tribute … to assay something greater. For me, a moment like finding the dead luna moth was both one of “travel and exploration,” as you note, not just for the ways that it moved my mind into a childlike space of inquiry, curiosity, meditation on the thing itself, but because the moment also had a humble and grounding effect on me as a writer—a writer keenly aware of influences such as Virginia Woolf and Annie Dillard who felt as present in my experience of discovering a moth, as I remember feeling present in their descriptions of the moths they witnessed.

Again, as far as an “occasion” for writing an essay goes, this was a big one. An opportunity to step into conversation with two women writers I admire, to explore a similar premise—albeit in a wholly different space, circumstance, and time, and to pay homage to a tradition, through observation and detail, of speaking to our preoccupation with life and death.

EB: The essay “Still Life with Chair” was published in 2015 in a slightly different form in The Normal School. One passage reads: “The simple presence of a chair, like the unbridled promise of life when we are young, is a common assumption: we trust that the structure will hold us. But what if a chair is pulled aside, what if it breaks suddenly beneath you?” How does this idea help you with writing?

JP: I’ve never thought of this idea in direct relation to writing before, but it’s an interesting question. “Still Life with Chair” is an essay that weaves in reflections on chairs, both as an object and their various depictions throughout art history. The piece centers around an accident and focuses on the notion of unexplained loss as well as the promise and excitement of youth, among other things. In the essay, the idea of a chair being pulled away, much like suddenly breaking, serves as a way of reflecting on the sense of uncertainty that can result from unexpected, seemingly random, experiences.

Accidents tend to erode one’s sense of trust in the world, to undermine the things we hold dear, and underscore the ways in which we may often take those things for granted—much like the way we tend to overlook everyday objects and artifacts. If I were to apply this idea to writing, it would likely present a call to greater awareness, a refusal to take for granted even the smallest moments or details that compose our experiences. Or, to go a step further, a refusal to take for granted how many moments can slip by without satisfying a need to write, without fulfilling a commitment to keep going, before losing those moments to days-gone-by and essays-not-written, to a stubborn misfit silence.

I’ve come to believe that sometimes we need a dose of the hard lessons in order to see clearly all of the things there are to be grateful for; we need a slap in the face to get our minds right; sometimes we need to know that although the structures that hold us might break and send us spiraling, at some point we’ll get up again.

EB: When reading your book, I kept feeling like I was escaping into a series of galleries where each essay was a room showcasing little pieces of you. You mention in numerous sections of how you observed different sculptures in galleries. How did those gallery visits inform your writing process?

JP: Art has had a great influence on my writing process. I have a deep appreciation for museums and galleries and the role they play in providing space for art to be widely viewed, studied, and revisited again and again, which is something I’ve grown accustomed to doing—particularly when I’m writing. For me, viewing art is an exercise of attention, a process of giving myself over to observation and allowing new ideas and meditations to surface as a result of the simple act of looking.

Many of the essays that became Lost Wax were written or at least partially drafted during a time when I worked in an art museum. Greek and Roman Sculpture, Egyptian Art, European Painting, Modern and Contemporary Painting, American Decorative Arts, Musical Instruments—the vast collections found in an encyclopedic museum contain, for me, a remarkable capacity to egg me on in the writing process. As an essayist, I tend to feed off of other surfaces—ogle and wonder and scrutinize things that, when given the chance to truly observe, often lead to the gleaning of a new idea, a line of language or description, a memory or association that often becomes where my writing begins. Museum galleries are one of the few places I have found that afford such time and space to stare without shame, to look unabashedly close at something—anything, really—until you find what you have are trying to say.

EB: To close, what projects, writing or otherwise, are you working on now?

JP: I have been working on a new series of essays that explore the concept of inheritance through an extended meditation on a range of objects.

Jericho Parms is the Author of Lost Wax (University of Georgia Press). Her essays have appeared in Fourth Genre, The Normal School, Hotel Amerika, Brevity, and elswhere. She is the Associate Director of the MFA in Creative Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts and teaches.

Elizabeth Bolanos was born and raised in Fresno. She is a first-year MFA graduate student at Fresno State pursuing Creative Writing with an Emphasis in Publishing & Editing. Her focus is fiction. She enjoys reading and gaining inspiration from all genres and forms of art.

Photo by Josh Larkin

It all began with a headache. Not a stranger to migraines, though, Christine Hyung-Oak Lee thought nothing of it until, a few hours later, she literally couldn’t see straight and, eventually, lost the ability to communicate; her speech limited to short sentences. This was New Year’s Eve, December 31, 2006. A few days later, Lee was taken into John Muir Medical Center, where it was confirmed that she had had a stroke. Lee was just 33-years-old.

Lee recreates that night and the harrowing days, months, and years that followed in her debut memoir, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember. Ahead of her appearance at last weekend’s WordFest, which was hosted, in part, by The Normal School, Lee and staffer Mary Pickett chatted via email about sharing trauma, the realities of letting your work go, and getting the most out of your writing experience.

A Normal Interview with Christine Hyung-Oak Lee

By Mary Pickett

Mary Pickett: We just passed an anniversary for you - Your debut memoir, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember, was released last Valentine’s Day (Feb. 14, 2017). How have things changed for you within this past year?

Christine Lee: Thank you for recognizing that anniversary.

It has been a year of new experiences. And mostly, lessons learned.

There were amazing things that happened: I had the opportunity to meet and interview with Scott Simon on NPR and had my book reviewed in the New York Times. Those are dream scenarios. And most heartwarming of all—I received encouraging emails from readers.

But there were also so many things I’d not anticipated. Including the changing of my identity—for so many years, I’d been unpublished, and suddenly, I was an author of a book. And the only difference was one day in my entire life—and I had to say goodbye to that writer and embrace a future I’d only dreamt of. So, I was also strangely in mourning.

It’s like when I finally got divorced after four long years of paperwork and court appointments and many talks with lawyers. I seriously thought I’d be overjoyed when the divorce was announced. But when the judge began saying, “I dissolve the marriage of…” I broke down in tears in court. I did not expect that reaction. But you know, grief is part of moving forward and part of achievements—you say goodbye to the past.

It has also been a year of becoming more of a private person—which is ironic, because I just put out a memoir with very personal thoughts and feelings. It is because of that very fact that putting out a book can be a very bruising experience and so I re-prioritized yet again and focused on my inner life. This meant holding dear my closest friends. This meant focusing on my daughter and partner more than ever. This even meant ramping up my urban farm and falling in love with beekeeping. You know—non-writing stuff.

MP: I’m intrigued by your above description of book publication as a “bruising experience.” Can you tell me a little more about that? Might this experience occur only within nonfiction?

CL: I can only speak for my experience with my memoir, because my novel is still forthcoming. I hear publishing a novel is just as bruising for fiction authors, though. Maybe it’s bruising in different ways, because we each have different expectations that might not be met. You’ve spent a lot of time alone writing something for a very long time—maybe a year, maybe ten years, before releasing your dreams and expectations out into the world for judgment. I think in some ways, the MFA workshop is boot camp for that experience—your work, when read by others, is no longer your own. It is absorbed by different minds and it becomes something different altogether.

It’s heartwarming and, also, heartbreaking. Upon publication, your book is no longer your very own. Your book has its own life.

Publishing a book isn’t going to make you happy if you weren’t happy before you published the book. It isn’t going to open doors if you weren’t opening doors for yourself before you published the book. It doesn’t change who you are. To me, it’s like getting married; marriage in and of itself isn’t going to make or break a relationship or change a life. The work is the work. The love is the love. The passion is the passion.

MP: One of my favorite lines in your book is: “This book is about my stroke, but the stroke helped me come to terms with other traumas….” One of which, being your divorce. How did you decide to share these traumas with the world?

CL: I couldn’t not share the related traumas. My 14-year-old marriage (18 year relationship) fell apart and I was overcoming postpartum depression, and in my misery, I kept looking back at the stroke and the lessons learned therefrom. They were inextricably linked, especially at that time. So, I had to write them down. There is universality in the particular and I hope my readers, whether or not they’ve overcome a medical trauma, also glean helpful lessons from Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember.

MP: Was anything off-limits within this sharing?

CL: I did not share anything about the acute particulars of my separation. I wanted to prioritize my daughter’s wellbeing and that meant not tearing down her biological father. I wanted to write a book about which I’d feel zero regrets.

MP: You have written both nonfiction and fiction. Do you prefer one genre over another? Does genre classification matter?

CL: I really enjoy both fiction and nonfiction—though fiction is my first love, and there is always something special and unique and vulnerable about the thing for which you first feel passion.

Though both genres require craft, they have different requirements. Nonfiction has a hard line in that you must tell the truth as you experienced it. And because you are narrating facts, there is a great burden of curation on the writer to tell the story. You must pick from what you have been given.

Fiction does not have the burden of fact-telling, but it’s not any easier. I like to say that creative nonfiction is about describing the knife and slicing your wrists. Fiction is about building the knife and slicing your wrists.

MP: We first met in the Spring of 2016, when you were a guest lecturer for my Fresno State MFA fiction workshop. I still can’t believe that you drove a total of six hours every Wednesday (from Berkeley to Fresno, and back again)! That’s real dedication to teaching. How does your teaching inform your writing?

CL: That was an epic commute. I can’t believe I did that, either! I ate a ton of Hi-Chews during those drives out of sheer boredom. I think I ate about six packs of Hi-Chews each week and I listened to a lot of podcasts.

But I really did enjoy my time in the classroom with you. Part of the reality is that teaching takes time away from writing—and that is the dirty secret that many writing teachers won’t share. But the other reality is that teaching helps my writing, because by iterating theory and craft to others, it helps me refine my own process and awareness.

MP: What are some of your favorite podcasts?

CL: Dear Sugars, Reading Women, Story Makers Show, and TED Radio Hour.

MP: Can you tell me about your latest writing project: your upcoming novel, The Golem of Seoul?

CL: My novel is about two Korean immigrants who travel to the United States in 1972 to find a long lost relative. They build a golem out of a tin of soil they’ve brought with them from North Korea to help them out. It is a cross-cultural retelling of an old story.

That’s what the novel is right now, but I just got editorial notes back from my editor, so that may change.

MP: I want to thank you for coming back to Fresno State to lead a craft talk and read from your work during WordFest. The focus of your talk was on building worlds - which, as you said, can be applied to both fiction and nonfiction. Do you find the world building process similar for both genres?

CL: I think the world building process differs for each and every book and story. Each story and narrative requires different things out of the writer each time. In one story, you might be intimate with the physical terrain, but have to explore its emotional connection. In another story, you might be imagining a world with which you're not familiar and have to build from scratch, which in some ways means freedom, and in other ways, means more work. I wish I could provide predictive information, but it really is a new start each and every time. But you do hope you've built more muscles and tactics and strategies as time wears on.

MP: You turned the talk into a bit of an art class, by having us build our own worlds out of clay. How did you come up with this exercise? Is this something you might recommend as part of the writing process?

CL: I thought that after sitting and listening in your seats all day that it would be nice for you to get your hands literally dirty. I am very aware that students learn things in different ways - some of us through watching and others through physical experience. And I am aware that playing is very important to art. So, I was looking for an exercise in which you could have "hands-on" experience.

This turned out to be a literal hands-on exercise. I am going to credit Victor LaValle for this exercise. While I was writing the first draft of my novel, Victor suggested I go and build my own golem as my characters do. So, I went out and got some clay and sat down, expecting very little out of the experiment. I learned that it's not so easy to build a little figurine. I learned that it is an emotional experience. I got to embody my own characters and understand what it was like to be in their world - the questions that go through their mind and even the order in which one would build body parts.

Some people don't have to have the kinetic learning experience. But many of us do to some point. And we need all-hands-on-deck to write a book. We need to learn in as many ways as possible. We need to engage in as many ways as possible. So yes - if you're stuck or even if you're not stuck, go out and build something. If your characters are in agriculture, go plant one of the vegetables or fruits they're tending, whether it is a strawberry plant, cotton plant, or an artichoke. You don't have to plant an entire field, but you have to know what it feels like to plant something, to feel the soil, and to see what it looks like when it first pops up out of the soil. You even have to feel and understand what it's like to watch a plant die; so, if you fail at growing the thing, there's opportunity in that, too. If one of your characters is a housekeeper, go out and clean a friend's home. See what it's like to be tasked with something and to wander around someone else's house and have to clean a mess that isn't your own. Embody the experience. Put yourself physically in your world's space, to the extent that it's possible.

Born in New York City, Christine Hyung-Oak Lee is the author of the memoir Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in The New York Times, Zyzzyva, Guernica, the Rumpus, and BuzzFeed, among other publications. Her novel, The Golem of Seoul, is forthcoming from Ecco/Harper Collins.

Mary Pickett is a third-year MFA fiction candidate at Fresno State and Senior Associate Fiction Editor for The Normal School.

The Bubble Wrapped Heart By Geoffrey Line

When Petra was little her papa hurt her, and so she put her heart in bubble wrap. Layer upon layer upon layer of unspooled, suffocating plastic that padded her vital organ in an impenetrable fortress that could go anywhere, endure anything, no matter the fragility of its contents. Pigtails, lollypops, and monkey bar skills, that was her, but she performed her brutal surgery all the same.

Read MorePanel Discussions: Men of Yesterday by William Bradley

I didn’t know much about Curt Swan when I met him—only that he’d penciled a lot of Superman and Superman Family comics during the “Silver Age” of comic books—that hazily define time that covers the 1960s and early 1970s. I knew that he was important, that he was someone I ought to know—the way I felt like I probably needed to listen to more John Lennon and read more Ernest Hemingway.

Read MoreBrands and Promises by Alex Khansa

Precious moments. That’s what life is all about. Your first step. Your first word. Your first bike ride with no training wheels. The first time you hold a pretty girl’s hand. When she rests her head on your chest and you smell a fruity scent on her braided hair. The new or hand-me-down car you get—that first gear you shift, grabbing the wheel with both hands, grandma style. It’s beautiful. But that’s not my story; mine can be summarized in five-year increments, not in fragmented moments.

Read MoreJon Kerstetter’s memoir, Crossings: A Doctor-Soldier’s Story, offers a new and empathetic perspective to the ever-growing body of work exploring our forever wars. While the book centers on Kerstetter’s experiences in Iraq, Crossings moves far beyond war stories. With a physician’s precision and skill, he illuminates his personal crossings—civilian to doctor to soldier to patient to writer—and challenges us to investigate our own transitions. In this examination of a compelling life, he takes us on a journey that delves into liminal places at the core of our humanity. Kerstetter and I have walked some of the same ground in Iraq, and as a husband, father, veteran, reader, and writer, I found much to admire in Crossings. This is an important and gripping book that chronicles the costs of war and how family, love, art, and tenacity can bring hope, healing, and redemption.

Kerstetter’s name first appeared in The Normal School’s pages when he won the 2014 Normal School Nonfiction Prize with his essay, “Learning to Breath,” which eventually became Crossings’ prologue.

A Normal Interview with Jon Kerstetter

By Brandon Lingle

Brandon Lingle: Tell us about how you came up with the crossings metaphor as a unifying idea for your book?

Jon Kerstetter: That was a late development. I had, in the earliest stages, envisioned the book as a work that played on the practical and literary tensions of being a doctor and a soldier, (the first title was Soldier-Doctor) but in the course of developing it, I realized there was much more to the story because there was much more to me. Who was I in the most complete sense? Well, soldier and doctor certainly, but I was also a Native American with a different cultural perspective, I was a father and an older man. I was a stroke survivor and a patient during the entire time of the writing. Those were the parts that I had to reveal if the memoir was going to be true to my life and the pivotal events in it. During the first four years of the project, I struggled with the unifying theme and the narrative arc. It was only during the final three years that the notion of crossings really hit me as a central metaphor. What had I done during my entire life? Pushed against the boundaries that tried to define me. And I pushed them hard until I was able to cross them all. Crossings, quite literally, were in my DNA. Once I understood my own history, the crossings became clear, both as metaphor and milestones.

BL: I’ve heard surgeons say medicine is as much art as it is science. How do you think medicine and science inform your art?

JK: The core of medicine and science rests in the ability to make precise observations upon which diagnoses and therapeutics are based. To me, that is also the essence of good writing—keen and precise observations about characters, events, and settings followed by thoughtful interpretations of what has been observed. When I first started writing, I tried to write profound meanings for the reader. The writing was forced and unnatural. My mentors gave me some excellent advice: ‘instead of trying to make meaning, focus on making sentences. Give all the details of who, what, where, and when.’ That was great advice. I then drew on my medical training and began writing exactly what I observed, the color of the room, the sound of a bullet, the smell of battle, and when I made the change, my writing came to life and was precise and accurate. The meanings I sought to provide for readers then flowed naturally out of the story and its details, much like a diagnosis logically flowed out of astute clinical observations.

BL: Proximity and distance are threads that run through the book. You wrote, “I learned to get close enough to patients to show empathy and compassion while remaining detached enough to move from one case to the next with the understanding that medical science could not save every patient.” And, later, “remain detached in spirit without being distant in practice.” How does the ability to detach impact your writing?

JK: That detachment was critical in my writing. It allowed me to gain needed distance from emotionally laden stories that tended to trap me in a rather sad and depressed mood. War is a sad state of affairs, but to write effectively about it, about any difficult and emotional encounter, a writer needs to first convey the details of exactly what is seen and experienced. Doing so helps readers see and feel and hear as if they were real-time observers in a scene. That is the “show versus tell” or the “show and tell” of writing. With respect to difficult and highly emotional stories, the ability to move between the proximity of emotion and the distance of details is imperative in conveying the full range of our human experience. Writers are translators: we take one language of human experience and translate it into another language so others can understand us. That translation is never easy. The Triage chapter in the book was originally published as an essay that took me a year and a hundred drafts to complete. In writing the first drafts, I would slump my shoulders, weep, and allow myself to be overcome with grief. I had to make a transition from the participant in the story, to the writer of the story. Without that transition, I was too close emotionally to describe the events in the manner it deserved, with the details that allowed readers to experience firsthand the gut-wrenching challenges of medicine practiced in war.

BL: You note your life’s ironies, “A doctor training to become a soldier, a Native American in the modern cavalry whose roots extended all the way back to the Indian Wars.” Some would cite the ironies of our continued interventions in the Middle East. How does your work help you make sense of these complicated relationships?

JK: Life’s ironies. What would we do without them? In a sense, life merely offers us a sequence of events. We make the interpretations and see the ironies, the tragedies and the humor. We see the love and the hate and the indifference. When I write, whether essays or chapters in a book, I objectify my experiences on paper and then come back months later to encounter them much as a first-time reader would encounter them. That’s why it’s important to let material sit for a while between revisions, so one can get as close to objectivity as possible. And that writing/reading/revising process is the most rewarding kind of experience. It allows me to hone my views, challenge what I believe, see the subtleness of some ironies and the hammering force of others I may have been blind to. Case in point: my assignment to the Cavalry as a medical officer. I knew about Custer’s last stand in an academic, historical sense, but when I was revising that chapter about joining the National Guard, the rich details of my encounter with the commander, his black Stetson with its gold cavalry band and the image of Custer on horseback gave me a fleeting sense that we were playing “Cowboys and Indians,” and the irony hit me. How far had we both come. One needing the other. Now fighting together, yet known in history as fierce enemies. A modern Native doctor in the modern Cavalry. Our ancestors might weep or they might laugh, depending.

BL: You sought out dangerous and necessary humanitarian work in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Kosovo and wrote, “disaster medicine forced a reliance on the ‘thinking’ aspects of medicine rather than the ‘technological’ aspects…” and “I needed those patients just as they needed me. Their need for a doctor fueled my need to be a doctor. Everything I did for them mattered, and as detached as I had to become for professional survival, I became attached to those patients; I was the doctor who gave hope and even laughter with medicine. I lifted patients’ spirits and by doing so, lifted my own. There was a feeling that unified us, patient and doctor, against whatever calamity was trying to destroy us, so in the end we all survived together.” How does writing compare?

JK: Writing defines writers. I am now a writer who is as defined by my writing as I was by my career in medicine. But the defining is not one way. As in medicine and soldiering, I have become part of cadre of people who define writing by pushing boundaries with my unique perspective. We writers all have that opportunity; we shape our craft at the edges where it needs redefining, we bend the rules, twist the structure, challenge the paradigms of what it means to write and create. As much as I need writing now, I have a sense that it also needs me. I have my need to bring a new way of talking about combat and healing and loss, a fresh way of dealing with tragedy and hope. And the canon of literature needs that new approach, needs all of our new viewpoints. I need writing; it needs me.

BL: You spend time discussing the spin-up for your first Iraq deployment… the call up, balancing family with deployment preparations, and training. Then we land in Kuwait. The transition from home to war is a major crossing, and I’m interested in the creative choice to leave the physical trip out?

JK: That trip caused lots of mental anguish in terms of the prospects of putting all that I had learned in training to the test of real-time war medicine. But the anguish was mostly internal and I struggled with its usefulness in the work as a whole. I had written a separate essay in which I explored that physical trip to Iraq, but I had also written about my physical medevac out of Iraq. I decided to maximize the impact of the arrival transition by compressing the time: the reader sees the home preparation and then Bamm! Arrival. That transition is abrupt compared to the months of training preceding it, and the abruptness, I think, adds to the gritty effect of unexpected nature of war. I could have gone the other way and included the trip to Iraq, but that was a choice I made in pacing the story. And that brings up a good point, pacing is a key element in writing. The writer faces many difficult choices in tuning the pace of a story. An essay with the same thematic material may have one pace, yet as part of the larger story in a book, the same material may require different pacing and a different strategy. Choosing what to include or exclude in a story is always a debate.

BL: The entangling nature of war surfaces throughout the book. After orchestrating the autopsies and transfer of Saddam’s sons, you wrote, “I felt my refusal to witness the bodies of Uday and Qusay Hussein was my way of protecting my family from the entangling influences of their evil.” I appreciated your candor and understand this act of looking away. Do you think our country looks away too much from the truths of war? How do you think our society should recount and discuss war? If our society was more candid and open about the costs, would we be less apathetic when it comes to sending people to fight overseas?

JK: I think society as a whole looks away from the horrific and difficult truths of war. It is one of the ways we tell ourselves war is not real, that we humans have not crossed into inhumanity. Of course, we know that is self-deception on a grand scale. The role of war writers and war correspondents is that of truth telling—we writers bear the responsibility of telling about war from our unique vantage point. We are the ones who must call to society, sound the warning bell and show the true cost of war and our inhumanity. Hopefully our candor makes people think enough to challenge our politicians and military leaders as to our future roles in conflict. We all know that some wars must be fought; that will perhaps never change. But what must change is our proclivity for conflict leading to war. We, the military writers must become the lens and the mirrors that show the price of apathy. If we continue turning out excellent literature of war, we have a better chance at driving a cultural dialogue that focuses on the true costs of war. That is why it is important to keep writing and keep pushing our readers.

BL: On war’s insidiousness, you wrote, “In one moment you recalled the good things of home, and in the next moment the things of war and its inhumanity would creep in and destroy a perfectly beautiful and peaceful memory.” Can you discuss how writing this book affected these intrusive memories of war for you?

JK: Well, the intrusions were no small thing. They were the cost of writing about war. Writing makes writers relive experiences and when those experiences make writers plunge headlong into personal conflict and pain, the process takes on a horror all its own. There were several times when it was just too difficult to write. And frankly, some of the most difficult pieces I wrote were difficult for my first readers to get through. I had to learn to write in smaller, manageable chunks of the most gruesome war scenes. I even debated about leaving the most difficult scenes out, but that felt like a violation of the truth and my writing task. I decided that if I was going to write about war and all its ugliness from a physician’s point of view, I had to tell the truth to remain faithful to the craft of writing, but also to the men and women under my care who lost their lives in a most horrific way. My memories would become the memories of readers who trusted me to write the truth… and that became the balm that helped me deal with the intrusiveness of the horrific scenes of war. Yes, there was pain, but the telling of the truth helped in the comprehension of it all.

BL: This vignette about a dying soldier... “The general laid his hand on the expectant soldier’s leg—the leg whose strength I imagined was drifting like a shape-shifting cloud moving against a dark umber sky; strength retreating into a time before it carried a soldier into war. And I watched the drifting of a man back into the womb of his mother, drifting toward a time when a leg was not a leg, a body not a body—to a time when a soldier was only the laughing between two young lovers who could never imagine that a leg-body-man-soldier would one day lie expectant and that that soldier would be their son.” Heart breaking and beautiful, this section captures war’s costs. What can we learn from this loss?

JK: I think the most poignant section of that chapter is the connection I made with the soldier and his mother, with his birth as it relates to two lovers who will one day realize that their greatest joy has become the source of their greatest sorrow. That is the part of war that makes soldier’s human, on both sides of the enemy lines. We are all sons or daughters of someone who loves us; and that relationship will cost some parents and families dearly. The pain will never die. That is the absolute tragedy of war, the loss, the terrible unending loss. That is the part of war that families must shoulder when nobody is looking, when all the Homefront support dies down. It is the part that makes for divorces and drunkenness and depression for survivors. It is the part that no medal or flag ceremony at a military funeral can erase. It is the part of war that continues even when the armistice is signed and armies return home.

BL: Regarding the dying soldier, you wrote, “If this were my son, I would want soldiers to gather in his room, listen to his breathing. I would want them to break stride from their war routines, perhaps to weep, perhaps to pray. And if he called out for his dad, I would want them to be a father to my son. Simply that—nothing more, nothing less—procedures not written in Department of Defense manuals or war theory classes or triage exercises.” How can we develop this type of humanity in our society?

JK: At the heart of that moment I drew on my experiences as a father of four children. And in that, one thing defined my role: love. In that singular moment, love was needed more than all the other things we could give a dying soldier. He didn’t need more medical expertise, no military honor and no blessing from a chaplain. He needed the tenderness of his father holding him in the grasp of loving arms. How do we develop that kind of compassion? That is the stuff of being human and being a parent. It is the stuff of deep reflection on what things are truly important in our lives. Yes of course, as members of the military community we value the mission and our commitment to each other, but in the final hour, in the final moments of our understanding of what it means to be human, we must come to value our love above all else. Not an easy thing to do, and doing so in the crucible of combat is always a challenge, but I think it is exactly what defines us as human and gives us hope that we shall survive from one generation to the next, both as soldiers and as citizens.

BL: Tim O’Brien says “True war stories do not generalize. They do not indulge in abstraction or analysis,” and “It comes down to gut instinct. A true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe.” You’ve written some stomach believing moments in this book. One example that stays with me, “As I slid the remains across the stainless steel table, the sharp edges of bone and the tiny rocks embedded in the tissues made a scratchy, metallic sound. I felt the sound in my teeth.” How do you distill such complicated images?

JK: I distil them by working the memories until the details become so clear I can smell the smells and hear the scratching. That is the work of asking questions of the event and revising to get the details just right. The mass of details that can be remembered is truly amazing and it becomes my job to sort through the most telling of details to form the images that carry the most power. When revising, details that are most powerful bubble to the top because they are usually the ones that elicit the most emotional or visceral response. Feeling sound in your teeth, like the scratching a chalkboard, is a sound that we all detest. Equating that kind of “universal” experience to a unique medical experience in battle is one of connecting experiences through common language. Again, I see my role as one of translation. In order to bring readers into my emotional landscape, I must translate things I see into something they can see. And precise control of words and details is what I use to get that done.

BL: The rendering of your stroke and its aftermath offers powerful insight. The moment when you’re looking at the MRI images, and you think, “Those brains have stolen my name,” really hit home. Did you find it difficult as a medical doctor to write about medicine for non-medical professionals?

JK: It’s somewhat difficult. Medicine contains its own special language and doctors are guilty of being so deep into their own specialties that making sense of the very complicated nature of disease and trauma if often not their forte. I had to learn not to speak in medicalease but in language that could be understood. Yet in that, I still used medical terminology without necessarily defining all my terms at the risk of slowing pacing. O’Brien does the same thing in describing things soldiers carried. He does not define every technical military thing and it works to the benefit of his readers. Much of what may be said in medical terminology can be understood contextually without having to know the exact definition of a medical word. More of the issue of writing about medicine came as a result of writing about something from which I was estranged. I was no longer a practicing physician, and the difficulty of using medical language only heightened the distance between me and my love of medicine.

BL: Books and writing helped you during your recovery. I appreciated how writing helped you understand “the dual nature of trauma, real versus remembered.” Do you want to write more about Iraq and your recovery?

JK: I want to write more about recovery because there is much more to be said about it, much more that I learned about the process. I might write another book about war, but I need to rest a bit and consider the emotional cost of doing so. Recovery is different; it is more about healing and hope and the future, and that excites me. One thing I and my healthcare providers learned about my recovery is this: it was unique in that writing had some unforeseen consequences in terms of cognitive recovery and even PTSD recovery. A healing brain is stimulated by use, by thinking and processing. And what is writing but thinking and thinking and thinking. That has been the core of my recovery. Writing and thinking. If I can write about that in more precise clinical terms or even team up with one of my neuropsychologists, that may lead to some very fruitful writing.

BL: In therapy, writing helped you organize and understand your thoughts and experiences. Later you entered an MFA program to hone your craft and create art. What was that crossing like?

JK: It was crazy scary. At the time I entered the writing program I had a reading speed and comprehension rate at the 5th percentile of adults my age (60 at the time). I felt inadequate and ill-prepared to learn something I thought was so far out of my lane of expertise. I felt like an old man on skies with youngsters whizzing by me on a steep slope. I envisioned myself as getting tangled in the rope tow. But the program I attended promised to work with me, and they did. They critiqued my writing as they did other students and pushed me to focus and write better. The environment they created was accepting and challenging. That brings up a point about pedagogy. Teachers have the ability to influence the lives of their students, and the students have the ability to change the way they see and do things. That was certainly operative in my case and I was able to respond in kind to the teaching and mentoring that I received.

BL: The recent politicization of soldier’s deaths in Niger highlighted the civil-military divide in the national dialogue. How can we continue to build understanding in our society?

JK: I think we need to understand that the military is part and parcel of society. We get our mandates from the greater society from which we belong. We are charged with an imperative to kill and destroy, two actions that in a setting other than war, would result in criminal charges. It is that sort of binary social ethic in which the military must do its missions: we are members of our society and members of our military forces; we walk the ethical lines between being both soldier and doctor, soldier and father and soldier and mother. And society demands that we walk that line well. They are the senders: the military are the goers. They are both essential to our continuing existence and even our continuing peace.

BL: I see your story as one of strength, recovery, and resiliency. It’s not a “damaged veteran” narrative. Unfortunately, the “damaged veteran” stereotype still pervades our society. Many works about our nation’s forever wars perpetuate this image. How can we battle against this worn out storyline?

JK: I hate the damaged veteran narrative. It gives such a weak and worn out picture of who veterans really are. The entirety of military training, hopefully of life training, focuses on the ability to adapt and overcome and to interpret the ongoing battle, and if a change is demanded, a change of course follows. What is more demanding of change than a veteran with injuries, mental, physical or both? The veteran must change in order to survive and most do. We are not stuck in a corner of a room twitching at the slightest sound or incapable of learning. My story and so many more like it are the prime evidence that veterans are capable of learning and adapting to change, of moving on in terms of healing and recovery. One of the challenges in redefining the veteran narrative comes in the form of challenging some of the thinking at of healthcare providers who still cling to the damaged veteran model. That is changing as military medicine makes known all it has observed from the current conflicts, but the progress is slower than I would like to see. Interestingly, some of the most intriguing approaches to challenging old paradigms has come from the arts. Private non-profit groups have engaged veterans in plays, painting, paper making, writing and story-telling as forms of healing and growth. If veterans are to expect a different narrative, it may well be up to them to challenge the “expected” with their own stories. And that gives me great hope. As in the battlefield, I see strength and courage displayed among our veterans who face the enormous postwar challenges of healing and learning.

BL: Any advice for veteran writers?

JK: Yes. Write like your life depends on it. Take the time to reflect on all that you have experienced and then put in a first draft and then a second and a third…. When you get to the point where you think you have captured the essence of your story, put it down and revisit it a month later and see how it affects your emotional terrain. If it makes you laugh or weep or cry out in anger, you are on the right track. Give your writing to a very few trusted readers who can give you honest feedback. You are not looking for writing that is just good; you are looking for writing that disrupts readers and demands reflection, writing that is real and truthful, bold and risky. If your writing makes your readers pause and consider things they never considered, you might be done, otherwise, keep writing.

BL: What are you reading now?

JK: I am reading some histories of my tribe and visiting some military museums. Interesting how much can be learned reading those museum placards that you tend to brush over. They tell a story, the visuals and artifacts of a museum tell a story. I want to take more time to learn what they are saying. Currently, I am reading, Empire of the Summer Moon by Gwynne. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. I tend to think of histories as dry and boring, but in the hands of a master story teller the subject tends to come alive with meaning. Oh, and I finished Everyman, by Philip Roth. It was a Pen/Faulkner Award Winner. Both books, one nonfiction, the other fiction, challenge common presuppositions about their subject matter and in that regard are just the kind of reading I enjoy the most.

BL: What’s your next project?

JK: I am busy defining that now and will most likely go in the direction of writing about stroke recovery. I have learned so much in recovery that it seems almost imperative that I should share it. I am also working on some short essays in fiction. I know, essays are in the nonfiction column. But what if I could write one that uses fictional composites of characters and events to make the same points as its nonfiction counterpart. I say it can be done just as easily as a Native American physician can join a Cavalry Regiment in the U.S. Army. If I can entertain that irony, can I not entertain an irony of literary form? I think your readers know the answer.

BL: Anything else you’d like to add?

JK: Life is full of the unexpected. I never thought I would have a stroke. Never thought I would write a book telling about how I recovered, or write essays about my life as a soldier doctor. What I turn to now is legacy formation, not only for my family and grandchildren, but also for my readers. I trust I am doing that just as I did soldiering and doctoring.

Jon R. Kerstetter is a physician and retired U.S. Army Flight Surgeon. He is a graduate of the Mayo Medical School in Rochester, MN (Class of 1988). He was the in-country director of the Johns Hopkins program in Emergency Medicine in Kosovo and provided humanitarian medical care in the conflicts in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Kosovo and in the hurricane disaster in Honduras. After joining the Iowa Army National Guard in 1994, he served as a medical officer until his retirement in 2009. Kerstetter completed three tours of duty in Iraq with the U.S. Army as a combat physician and flight surgeon.

Dr. Kerstetter also holds an MS in business from the University of Utah and an MFA in creative non-fiction at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio. He is the author of the memoir, Crossings: A Doctor Soldier’s Story and his essays have appeared in literary journals including The Normal School, Best American Essays, Riverteeth, Lunch Ticket and others.

Brandon Lingle’s essays have appeared in various publications including The Normal School, The American Scholar, Guernica, The New York Times At War, and The North American Review. His work has been noted in five editions of The Best American Essays. An Air Force officer, he’s served in Iraq and Afghanistan. A California native, he currently lives in Texas and edits War, Literature, and the Arts. Views are his own.

Exit 105 by Lindsay Haber

Glen’s wasn’t one of those fucking cliché cancer stories. It wasn’t fighting for survival, lamenting with his wife and kids, telling everyone to go on without him. Glen’s was stomach pains that led to six weeks to live which was really four and a half, every moment of which he was fucking sick and despondent, and couldn’t walk for more than a few minutes, and could barely talk or swallow. When people would see him, they’d whisper about how terrible he looked, like he was already dead.

Read MoreIn regular life, Bich Minh Nguyen goes by the name Beth. She is the author of three books, all with Viking Penguin. Stealing Buddha's Dinner, a memoir, received the PEN/Jerard Award from the PEN American Center and was a Chicago Tribune Best Book of the Year. It has been featured as a common read selection within numerous communities, schools, and universities. Short Girls, a novel, was an American Book Award winner in fiction and a Library Journal best book of the year. Her most recent novel, Pioneer Girl, is about the mysterious ties between a Vietnamese immigrant family and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Nguyen has been a Bread Loaf Fellow, among other honors, and her work has appeared in anthologies and publications including The New York Times. She is at work on a series of essays about high school, music, and the Midwest, called Owner of a Lonely Heart. She has also coedited three anthologies: 30/30: Thirty American Stories from the Last Thirty Years; Contemporary Creative Nonfiction: I & Eye; and The Contemporary American Short Story.

A Normal Interview with Bich Minh “Beth” Nguyen

By Tara Williams

Tara Williams: In the event of a zombie apocalypse and your imminent evacuation taking only what you can carry, which books would you take with you to a remote island compound serving as the last bastion of literate civilization?

Bich Minh Nguyen: This is an incredibly difficult question to answer! Right now the answer might be: Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson; Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison; Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen; and if there’s room, Emily Wilson’s recent translation of The Odyssey.

TW: The resonance of the choice to build your memoir around food memories is fascinating to me, especially with the dual meaning of the word assimilation, with its social and digestive connotations. I'm curious whether you started your memoir with this central theme in mind, or if it evolved as part of your writing process.

BMN: It evolved, definitely. When I started writing this, I didn’t know it was going to be a book. It was just an essay. And then another essay, and another. I had no great hopes or aspirations. But then I realized that I kept returning to food, and that food moments were natural markers for time, memory, significant events. And that’s basically how the pages became a book—when I recognized that food was the main anchor and symbol. Every book-length project needs an organizing principle, and food became mine.

TW: It struck me as I was reading that you are a kind of pioneer in the terrain of establishing American identity space for people who are not outwardly Euro-American in physical appearance but for whom American culture is a dominant influence. What does being American mean to you? Do you think there are definitive American cultural traits beyond consumerism and pop culture?

BMN: This is a tough question in late 2017. I grew up thinking that to be an American was to have the privilege of freedom—of expression, of ideas, of movement. I grew up with this belief that surely America is the best place to live. That is now in question, in this current administration. But what’s also in question is the definition of “American culture.” Basically I’ve been taught (most people are still taught) that “American” = white, and that white is the norm and the default; everyone else is still expected to assimilate, and ask if they belong, and wait to be included. If there’s one good thing to emerge from this current political landscape/nightmare, it’s a growing national awareness that that old model doesn’t hold up and cannot stand.

TW: I notice after your memoir, you have published two novels. Could you elaborate on your choice to switch genres in your writing?

BMN: I studied fiction and poetry in college and grad school. I started writing creative nonfiction out of pure frustration with myself, because every time I tried to write about my family’s story through fiction it didn’t sound quite real—because it wasn’t! It took me years to realize that I needed the genre of truth in order to tell the truth. (This isn’t the case for all stories, of course, but it was for mine.) And then it was like I’d gotten something out of the way for myself, in my head, which allowed me to write the fiction I’d always wanted to write. People often think my novels are autobiographical but I’d say they’re probably 80% fiction; the autobiographical parts are mainly about setting. My next book, which I’m still working on, is a series of linked essays about high school, college, music, and post-refugee life; it’s currently titled “Owner of a Lonely Heart." I encourage every writer to be fluent in more than genre, or at least to explore or try out other genres. Doing so opens up possibilities and ideas, and sometimes we have to let the genre choose the work.

TW: In many ways, it seems the current presidential administration embodies and seems to promote many of the xenophobic attitudes you encountered as a child. Does this affect you in any way?

BMN: I think we are all affected by this, daily and deeply, though yes, people of color and immigrants are affected in a far more urgent way. The people I worry about the most are the ones whose safety and status are being threatened. The racism and xenophobia I experienced and witnessed in my childhood has not changed. In many ways, it’s gotten worse.

TW: Do you still eat junk food? If so, what, how often, and under what conditions?

BMN: I eat a lot of gummy bears. Does that count as junk food? I also love pizza rolls (except they’re Annie’s organic, which seems ridiculous even to type) and I’m a huge fan of bad pizza and frozen pizza. For the most part though, I have to admit that I don’t really eat the kinds of junk food that I dreamed about when I was a kid. I think for three reasons: once I had total access to it as an adult, the allure went away; as I grew more socially and politically aware, and more able to accept my own identity, junk food no longer held the same kind of symbolic power or value; and I realized most junk food just doesn’t taste good! For example, I haven’t had a Coke or Pepsi or any similar kind of soda in probably 20 years, simply because I don’t want to. They don’t appeal to me at all. I feel very grateful that my grandmother Noi taught me to have a good relationship with food—to think of it as something that can add joy and goodness to one’s day.

TW: I see your memoir has also been optioned for movie development, and I'd ask about that too, but I know authors don't always have much say in how such a project develops.

BMN: You are right that I have no say in any of this. I do think it’s very strange and kind of hilarious!

If people wonder about the use of the name Beth, I started going by Beth a few years ago as a social experiment to see how my life would change—if people would perceive me differently (and yes, they do!). I’ve been writing an essay about the experience, which will go into my next book. :)

Bich Minh "Beth" Nguyen received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan, where she won Hopwood Awards in fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. She currently directs and teaches in the MFA in Writing Program at the University of San Francisco. She and her family live in the Bay Area.

Beth Nguyen will be a Guest Artist in July 2018 for The Normal School’s Summer Workshop and Publishing Institute in Nonfiction, part CSU Summer Arts:

http://blogs.calstate.edu/summerarts/courses/the-normal-schools-summer-workshop/

[A note on pronunciation: Bich is pronounced like "Bic"; Nguyen, the “Smith” of Viet Nam, is pronounced something like Ngoo-ee-ehn (said quickly, as in one syllable), but most people tend to say "Win" or "New-IN" instead and that has become acceptable.]

Tara Williams is an MFA candidate in Fresno State's Creative Writing Fiction program. She has previously published nonfiction books and articles on natural healing modalities, and interviews with cultural icons including Leonard Peltier, Russell Means, Julia Butterfly, and former WIBF World Champion boxer Lucia Rijker, "The Most Dangerous Woman in the World."

When We Were Animals by Lacy M. Johnson

There was a time when we lived in a place that was green and alive, where trees grew together in clusters we called forests, where we grew food we could eat right from the soil, where we could swim in the creeks after working in the fields and the water felt clean and cold. We could swim in the rivers, too, protected only by our own skin, and in the lakes we could catch fish that we might cook over an open fire after the sun had set. We would gather logs for this from the forest floor, rub two sticks together until they smoked and then with our breath or a bit of wind, they would catch a flame and burn.

Read MoreFellowship Application by Joseph Rios

His other hand enters my space with fingers out

like he’s flying or the birds are flying or we’re flying or the truck is

flying; we’re birds now and I still can’t get this shit lit.

On Exhibitionism by Joe Bonomo

The tiny flat at 102 Edith Grove in west Chelsea, London, is located in a district that was derided, centuries ago, as the “World’s End.” The name still seems apt: from the looks of things, I could push my fist through a water-damaged wall pretty easily, but I’m scared of what I might find living behind it.

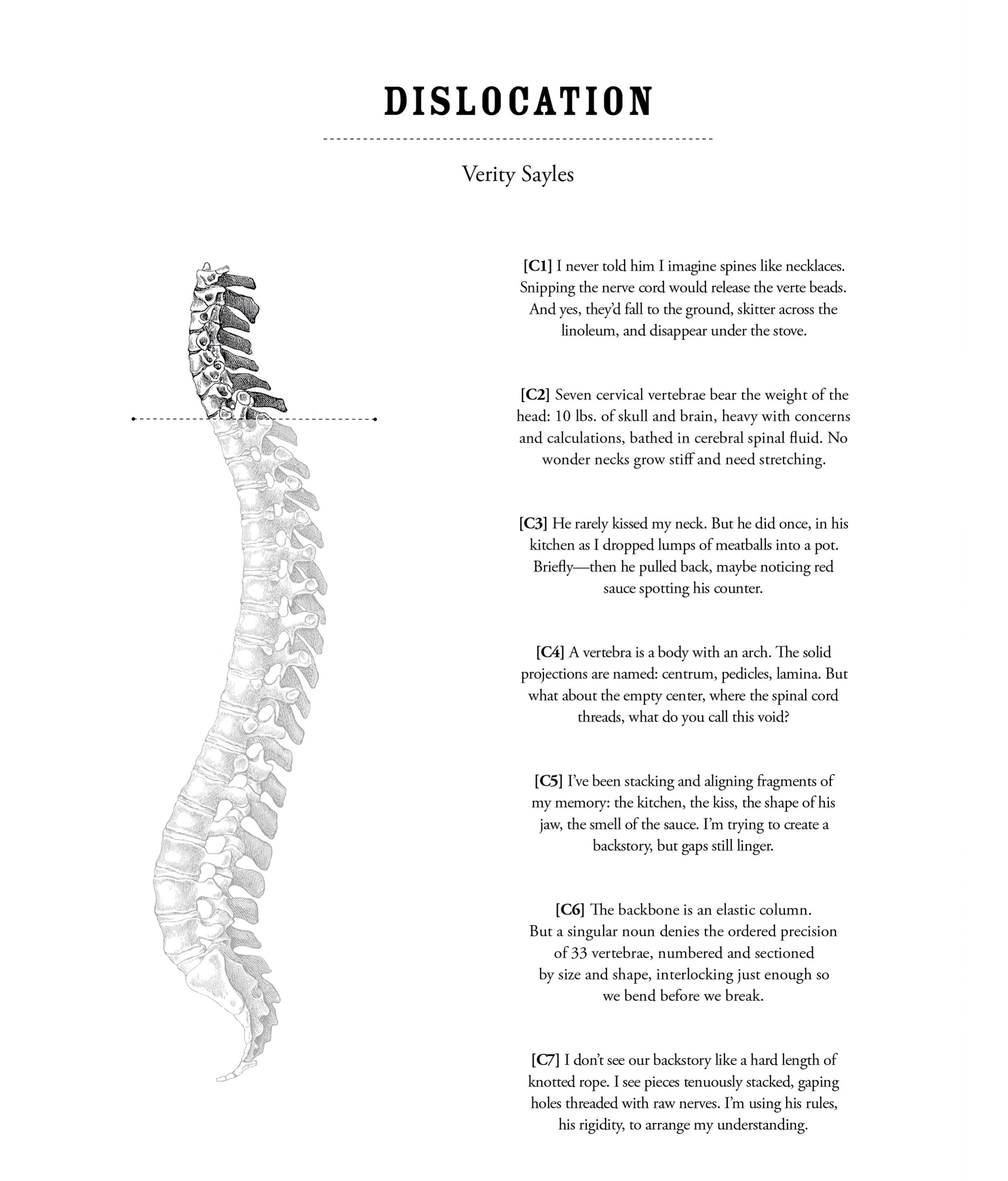

Read MoreDislocation by Verity Sayles

I never told him I imagine spines like necklaces.

Read MoreFemme Fatale by Felicia Rose Chavez

By Felicia Rose Chavez

Felicia Rose Chavez is a digital storyteller whose work features regularly on National Public Radio. She holds an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction from the University of Iowa. Former Program Director to Young Chicago Authors and founder of GirlSpeak, a literary webzine for young women, Felicia teaches creative writing and new media as a Riley Scholar-in-Residence at Colorado College. Find her at www.feliciarosechavez.com.

Schoolhouse at Corbin Hollow. Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. c. 1935

For You and I to See by Ryan McDonald