The history created by my four brothers, my sister, and me is rich and, as in every family, paradoxically commonplace and unprecedented: I am Me in large part because of Them, a random generation of closely-related DNA gathering under the same roof.

Read MoreSpeed by Maria Kuznetsova

We were spying on my parents. This was something we started a few weeks ago, when I noticed that they were worth spying on.

Read MoreThis is by Christen Noel

There’s a wrong way to leave a husband. A bag with clothes for one night. Half a tank of gas. A man crying on the floor.

Read MoreHere I Am by Xu Xi

He was not a zombie. Nor was he a ghoul, mummy, wraith, ambulatory skeleton, or operatic phantom. He wasn’t even 殭 屍 (geong si), a dressed-to-the-nines Qing dynasty vampire that could at least do an approximation of the Lindy Hop, transcending time and culture into the Jazz Age. However, he was clearly dead, or undead, if you parsed language to its core.

Read MoreWhite Birds by Jennifer Zeynab Maccani

What do the dancing white birds say, looking down upon burnt meadows?

Read MoreBodSwap with Moses by Wendy Rawlings

Manuela in scrub top and cheetah pants hasn’t even finished telling us what to expect from our new bodies when the Kenyans stride in on their excellent legs.

Read MoreTunnels by Marytza Rubio

Tunnels by Marytza Rubio

Tijuana

Epifania Fogata gave birth to three girls and four boys. My dad’s bedtime stories were full of defeated warriors and lost battles. Each night my grandmother asked him, What did they do wrong? How could they have won? When he was a teenager, he was entrusted with details of an inherited revolution. Two of his sisters were sent to schools in New England and one was sent to Paris. His brothers were taught to dig.

The walls along the border between Mexico and the Unites States disrupted the natural migration pattern of every living creature that couldn’t fly or swim. The mountain lions and jaguars suffered tremendous losses to their populations. They would have become extinct if not for the ingenuity and vast underground network built by the Fogata Landscape Company. When the mountain lions discovered they could travel under the freeways, their populations boomed and spread across Southern California. Moving the jaguars required meticulous planning. The Fogatas devoted decades preparing for their journey.

Nha Trang

After we all graduated from high school, I moved to L.A., my sister stayed home, one of my cousins became a trophy wife, and her sister backpacked across Southeast Asia. At the farewell barbecue before Miriam’s trip, she asked my dad if he had anything she could take for him when she visited Vietnam. Miriam told us about a documentary she’d seen about veterans who went back to the jungle to do a burial ceremony for the lives they’d taken—and for the parts of themselves now lost. She said she’d be happy to take something or bring something back if that would help him heal. My dad said he had nothing to heal, he was A OK, baby and served himself another plate of ribs.

Laguna Beach

Miriam’s sister Molly Bianchi (née Maricela Fogata) lived in one of those seaside cliff homes that was always in danger of burning down during fire season or falling off the edge of the earth during rainy season. The house’s fragility was part of its cachet: We can afford to be destroyed. The last time I visited that house I was twenty years old. My dad and I had taken a day trip to the beach and stopped in to visit Molly and her new husband. They were overseeing the construction of a gazebo for their telescopes. I saw in her face what my dad was asking me to fight. I saw my cousin get uncomfortable when the man working in her yard asked her a question. The question is in choppy accented English and it frustrates her, and when my dad interjects to interpret, she demands that my father, a veteran and her elder, speak English, please, and she and I never spoke again.

Santa Ana

On my way out of my parents’ house, I carried a blanket and wrapped it around my dad’s shoulders. He leaned forward in the lawn chair with his hands clamped together and his black wiry eyebrows tangled above his eyes. I let him know I was leaving and would be back the next weekend. When he didn’t respond, I moved closer to his good ear and repeated it. He said, “We’re running out of time.”

I took a deep breath and looked at my watch. There would be another train. I sat on the asphalt and joined him in his silence. Coddling him would only upset him and reminding him to have patience would anger him. I picked up a fallen leaf from the avocado tree and started to pinch off the browned pieces when the squawks of Santa Ana’s emerald parrots cut through the dusky sky, loud enough to distract my dad from his brooding. “Next time, bring me a dessert,” he said.

At the train station, a woman talking on her phone said it was “the strangest Monday ever.” She said global warming had made Friday the 13th come late, and what we really had to worry about now was Monday the 16th. As she said this, flecks of ash from the wildfire swirled around us and settled on the train tracks. The latest casualty was some billionaire’s multi-million dollar Laguna Beach house. One of his houses. The winds were forecasted to pick up again that weekend. The news would call it the “Santa Ana Wind Event.” It felt good hearing my city’s name on the news. It felt good to make people afraid.

A bearded man sat across from me on the train and asked for a piece of paper. He said he needed to write down an idea. All the passengers ignored him, so he started to recite his thoughts. I reached into my purse to find my notebook, hoping if he had something to scribble on he’d stop talking. I tore off a few sheets and handed them to him. The man mumbled I was “one of the good ones” before snatching the paper out of my hand and sprawling out in the middle of the aisle to write in silence. I looked down at my notebook and touched the embossed gold dove decorating the cover. The printed text below read We have so many dreams that we cannot talk about them all which I first misread as We have so many dreams that we cannot talk about them at all.

Los Angeles

When I arrived at the Little Tokyo station, my favorite man greeted me with a white rose. He asked me about my visit with the family and his voice jumped up an octave the way it did when he talked to children or homeless dogs. I didn’t respond. We walked past the sparkling metal and glass of the Japanese American Museum and slipped through a gap in the brick wall and down a narrow alley into our restaurant. This is where we came whenever we needed to feel right again. We never said it out loud, to do so would destroy the dream, but when we came here, my fiancé and I pretended we were in Tokyo. The lights of the Los Angeles skyline blurred away and the hammering steel blades of a vigilant helicopter warped the audio fabric of our conjured Japan.

Chicago, Denver, San Francisco

The explosions occurred in the late evening, when the office workers and executives had gone home and the cleaning crews had just arrived. One hundred and forty-seven dead. The targets were undocumented—it took years to uncover their true identities. A smaller explosion with a bottle rocket occurred at a nativity scene in Phoenix, but no souls were claimed. It was later determined to be an act of vandalism not related to the bombings, yet the image of the bubbling plastic of the Virgin Mary’s face become a symbol of national mourning to some, a declaration of war to others.

Himeji City

We got married in my parents’ backyard. The ceremony was celebratory enough to be special but subdued enough to be appropriate. Only his parents and my parents attended, and the next morning we boarded a plane to Japan. I needed distance from the States. Mid-flight, I told him I was going to quit teaching ESL because an old friend of my dad’s had asked me to care for his flock of trained pigeons.

Asuncíon

There are two Guarani phrases I retained from once working with a Paraguayan teaching assistant: Mbaé’chepa and Ipora. This knowledge and a valid passport were the two things that qualified me to record the vocabulary we’d use to build our code. My husband insisted on coming with me and I pretended to put up a fight but knew I would be more productive if I didn’t spend so much energy missing him. “Do you think is going to work?” he asked me the third week in. I only had a page and a half of words we could use. The phrases needed to be simple to scramble and decode, and concise enough to be legible on the small scroll we’d tuck inside our pigeons’ anklets. “Don’t worry about writing a complete sentence,” he insisted, but I couldn’t shut off my years of being an English instructor. “They don’t need to make sense, just get the point across.” He was right, words were all I needed: Coast, Hill, Beast.

Erupt, Earth, Run.

Santa Ana

When I was a newborn, there was a disruptive humming above the kitchen stove that concerned my mother. After complaining about the noise to my dad, she took me out for a stroll. My dad then dragged in a ladder from the backyard and crawled into the attic to investigate. The attic was a glorified crawl space full of itchy insulation, hot, dark, and only one way in, one way out. When we returned from our walk, the humming had stopped and my mom found my dad sitting in the living room staring at the wall, his face pale and wet. He told her he’d gotten trapped. He said that because everything was so dark, he didn’t know if he was left or right or day or night or city or jungle. When he heard his heartbeat echo in his ears like a desperate alarm, he decided to crawl backward, hoping that going in reverse would bring him to the edge of the attic door. If his foot dropped into an open space, he would survive but until it did, he believed he would not. He said this while holding me in his arms, rocking me back and forth and telling me he was sorry.

Montebello

My aunt Christina bought a cap-gun from the neighborhood paletero. As a joke, she fired it at my twenty-six-year-old dad when he was in the bathroom brushing his teeth. His shocked face drained to khaki, like when he got lost in the attic and when they told him he had to have surgery and when they covered his body several hours after I told him, for the second and last time, I loved him very much.

Santa Ana

When I was a little girl, my dad showed me how to set up pigeon traps in our backyard. We’d prop a cardboard box up by one corner using only a twig from our avocado tree, then tie a string around the twig. Dry cat food was the bait. The pigeons swooped down and pecked around the trail leading to the trap. They always did a hesitant little dance when they reached the outer rim of the propped-up box. My dad held his hands like a conductor and I held the other end of the string, waiting for his cue. “Uno, dos, y…” he’d draw out the “y” until the curious bird took its place in the center of the trap. “Tres!”

We set every bird free. The point of the traps wasn’t to collect pigeons. The point was to learn timing.

Tijuana

We arrived at Las Playas to scatter my dad’s ashes. His soul inhabited the altar in my mom’s living room and his name was engraved on a rock inside the Japanese garden next to City Hall. I insisted we wait until a full-moon weekend to scatter his ashes. My Tio escorted us out into the ocean on his boat, far enough into the water where the waves were still enough to reflect the sky, but close enough to shore that I could see the flickering lights of the candles on the sand. My sister read a poem and my mother gave the ocean a bouquet of gardenias and white roses. We poured my father into the moon. The boat lolled atop the rippling waves. We each heard our name echoed in the laps of water. I could clearly see him, smiling and clapping his hands: Uno, dos. Uno, dos. Uno, dos, y…

Laguna Beach

I broke my fifteen-year silence and left a message for Molly to join me in San Francisco for my sister’s book signing. She ignored me. Molly always wanted to be white so she never developed the instincts of a brown girl—there are unexpected gifts that accompany being hated and underestimated for who you are. One of them is sensing when you are in danger. Molly rejected us—and her full self—but our family still honored blood: The Fogata Landscaping crew did not connect her yard to the underground migration network. They did not spare her neighbors.

The sleek black jaguars roared as they burst through the ground, hungry and determined to reclaim their land.

Marytza K. Rubio is a writer from Santa Ana, California.

After Sandra Bland by Rachel Charlene Lewis

My partner is driving ninety miles per hour on our road trip from east to west coast when we’re pulled over to the side of an empty highway through Kansas. Her white, freckled skin is glowing in the early evening sunset, twists of pink and purple and orange billow uninhibited against the flat planes on either side of the highway. It is mostly quiet but for one or two cars passing us every dozen or so miles. They are mostly trucks, their drivers mostly older white men.

Read MoreFall by Marysa LaRowe

It started with the birds.

It was New Year’s Eve. We were sitting in the living room, watching the footage of fireworks in Australia, Tel Aviv, Berlin, London. Outside, people were setting off fireworks and bottle rockets of their own. You’d hear them whistle and pop every now and then, first far away, then close.

Read Morelast blues on red hands by Charlotte Covey

last blues on red hands by Charlotte Covey

the ocean stayed

silent; waves quiet, sand

still. windows half-opened made the world

blur— soft light, longing to

kiss my skin. your hands

on the steering wheel, paled

under pressure, a vein in your forehead,

teeth biting down on your

tongue. you washed over me, & i left

musty indoor air, ripped upholstery,

climbed down rocks & shells

to the place where the sand is

wet. it was the first of the

year; i held my

breath, standing at the water's

edge. i wonder if you were

watching me. wonder if you

drew blood when you bit, the way you

drew a circle on my neck with

your mouth. i wonder if you scrubbed

the stains left on the passenger

seat— rusted red, dripped from slits on

dimpled knees made with drunken

fingers & sharpened nails.

Charlotte Covey is from St. Mary's County, Maryland. She is currently a senior studying Creative Writing and Psychology at Salisbury University. She has poetry published or forthcoming in journals such as Salamander Magazine, Slipstream, The MacGuffin, SLAB, and The Summerset Review. She is co-editor-in-chief of Milk Journal.

The News by C. Dale Young

The potted ficus in the corner of Flora Diaz’s kitchen, the ficus barely four-feet tall and planted in a rust-colored ceramic pot, the one that she watered every six days had, for the first time in the almost four decades she had owned it, started showing some yellowing leaves. This did not escape Flora Diaz’s attention. Nor had it escaped Javier Castillo’s attention; he made a point of pointing it out when he first told me about that particular time in his life.

Read MoreRest Stop by Ana Crouch Ureña

Since I can remember, I’ve spent summers at my grandmother’s house on the coast. It’s a long drive, but this year will be the last time I make it. Mimi died in the spring. I was so upset, I even told my students about her. I was as surprised as they to find myself recounting how Mimi came to the US as a war bride. Really, I knew almost nothing about it; she never talked about that time.

Read MoreDreams in a Mirror by Gabrielle Bellot

It was a wonder none of us were expelled for breaking broomsticks over each other’s backs in secondary school, for hitting each other with thick foldable chairs we scarcely blocked, for using the tiny library on the lowest level of one of the two classroom buildings in order to wrestle each other instead of returning home on the bus or cleaning the chalkboards as the Brothers who taught our school lessons had commanded was our duty for that day.

Read MoreTwo Poems by Heather Lang

here’s a lastingness / of to crease and an ambiguity / of to fold.

Read MoreDown on the Ass Farm by Samuel Ligon

Remember how we’d handle snakes, diamondbacks and cottonmouths, praying we’d be okay someday and away from this place? We’d quote from scripture, glowing with the words we whispered: And they will take up snakes, and if they should drink lethal poison, it will not harm them, and they will place their hands on the sick. But we didn’t place our hands on the sick. And we didn’t drink lethal poison. We drank Father Tim’s whiskey and placed our hands on each other, saying yes to darkness and drink and the pleasures of the flesh. Do you remember?

Read MoreThe Making of a Hive by Amy Wallen

I hear a tiny tap, the smallest of sounds like a thumbtack has fallen on the tile. Or, someone very small is tapping on the window asking permission to come in. I hear another tap making me glance toward the stove. But I see nothing. I turn back to rinse off my one plate, my one glass.

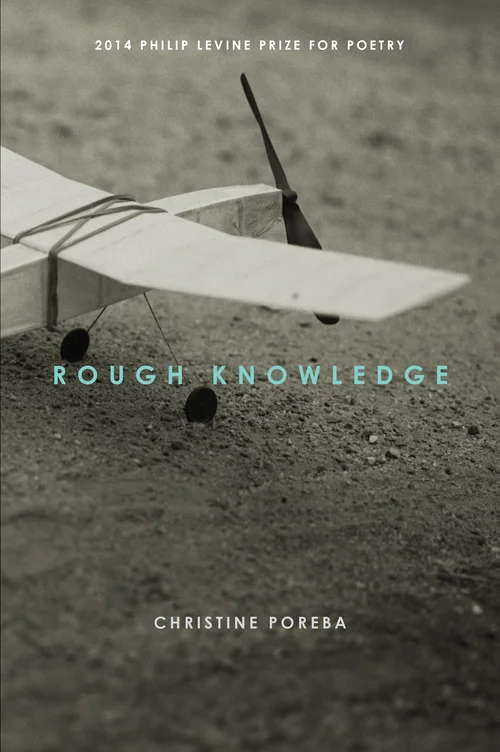

Read MoreNewly released from Anhinga Press, Christine Poreba’s poetry collection Rough Knowledge has been called a sweet and deeply thoughtful celebration of love, marriage, family, and friends. Her debut book won the 2014 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry contest, and final judge Peter Everwine called her poetry “a beautifully sustained and often surprising art of connections that takes nothing for granted.” Her work has appeared in numerous publications and anthologies, including The Sun Magazine, The Southern Review, Subtropics, and The Pinch.

Christine will visit The Normal School staff and California State University, Fresno on Friday, Feb. 26 for a reading and book signing in the Alice Peters Auditorium on campus at 7 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.

A Normal Interview with Christine Poreba

By Sean Patrick Kinneen

Sean Patrick Kinneen: How did you start writing, and who have been your poetry mentors?

Christine Poreba: I started writing poems in high school, most specifically for a senior project of our choosing for which I wrote and designed a booklet of poems called Refuge. [Sigh of slight embarrassment here.] My mom was an English teacher at the all-girls school I went to and she, a poet herself, agreed to be the adviser for the Poetry Club my best friend and I started. It was through my mom that I became aware of a high school poetry workshop happening at Academy of American Poets.

In college, I mostly wrote on my own but the summer before my senior year I took my first poetry class at what is now New York Writers’ Workshop but was then called The Writer’s Voice. My first class was with Donna Masini, whose handouts from that class 20 years ago — with ideas like writing down snippets of dreams and using freewrites — I still have and go back to. I remember her saying one day, “some days, only poetry…” in reference to how poetry can get us out of our funk, and the thought of that rang true for me. I also took a class with Elaine Equi, who gave me my first look at less narrative poetry, which helped widen my horizons. After that I took many wonderful classes with teacher Mary Stewart Hammond, who became my mentor. She both gave me confidence in my natural abilities as well as gave me tools and a strong inner voice to call upon in writing and revising poems.

SPK: What was the first poem you read? When was the last time you read it?

CP: One of the first poems I really remember reading, and also having recited to me by my mom, was "Spring” by Edna St. Vincent Millay. I never liked the season and my mom, who gave me an old copy of Renascence, one of my first owned poetry books, used to recite the opening lines to me:

To what purpose, April, do you return again?

Beauty is not enough.

You can no longer quiet me with the redness

Of little leaves opening stickily.

I know what I know.

I think the last time I read it was shortly before my son was born — in the spring — at which point my feelings about the season changed a bit.

SPK: Where did you grow up? Can you talk about how that place came to influence some of these poems?

CP: I grew up in New York City. I moved to Florida to get my MFA at the University of Florida in Gainesville and it felt like it took me a while to adjust to writing here. The energy and streets of New York were so much a part of my writing before I moved. It took me a while to get used to the quiet. I touch on this in my poem “Alight.” The city itself took on a more nostalgic tone in my work once it became the place I used to live. Ironically, the longer I live away from it, the more it takes on a separate entity in my poems. When I lived there, the very energy and happenings I observed became what I was writing about, but in Rough Knowledge it becomes part of my memories and takes on more distance. The last two poems of the first section of the book revolve around September 11th as I experienced it as a New Yorker. Since it’s where I’m from and this is a book about moving from where you’re from to where you are, it is an important part of these poems.

SPK: How long did you work on your Rough Knowledge manuscript before sending it out to contests?

CP: It was a long and slow process. I experimented with various compilations — one of which was a chapbook manuscript that included some of the poems from Rough Knowledge and was called Wide Stretch of Sky — after getting my MFA, but the skeletal version of Rough Knowledge did not begin to appear until about four years after that. I then entered it into contests for several years, and every year it changed slightly.

In 2014, I read an article by April Ossmann in Poets and Writers, Thinking Like an Editor: How to Order Your Poetry Manuscript, and that was very influential and led me to make significant changes before sending it out that fall, for, as it turned out, the last time! So, to answer your question, I worked on it for a few years before I first sent it out and revised it slightly for the first few years of sending it out and then more majorly the last year. I am definitely not a fast worker when it comes to manuscripts!

SPK: In your book, I saw subjects of family and memory, but even more subtle, I think, of death and rebirth, dark and light. Did those ideas inform the way you ultimately decided to organize this manuscript? Do you see all those subjects as being connected, cohesive in some way?

CP: This question feels connected to the last one for me. One of the things April Ossmann talks about is color coding poems by theme and using that as a guide for how to order the poems. In earlier renditions of the manuscript, I had often ended up grouping the poems chronologically in the order that events recounted had occurred. But because the poems themselves are narrative, I realized this sort of order didn’t really work so I decided to go with what Ossmann calls a lyric ordering, “in which each poem is linked to the previous one, repeating a word, image, subject, or theme.”

So yes, I do see all those subjects as being connected. Rough Knowledge is about a series of journeys for the speaker, from childhood to adulthood, from being single to being married, from an old home and old life to a new home and new life, from fear to calm again, from a simple every day thing to a huge tragic thing seen or read about. Also journeys of a house with its history of past inhabitants to taking on a new shape of its current ones and of a garden, going from empty to being filled with tiny seeds which may or may not grow. I chose “Toward Home” as the first poem because I felt like it introduced a bunch of these themes. After that, I wanted the book to have somewhat of an accordion feel, going back and forth between appreciation and wonder of a moment to fear and sorrow at darkness and loss since that is more what life itself is like rather than organized sections of different periods of time.

SPK: How did the title come about? Did the idea of transition from one life to another decide, perhaps unconsciously, the book being in two parts?

CP: I played around with a bunch of different titles, one of which was Containable. Rough Knowledge was actually the earlier title of the poem “The Turn,” which I see as being at the heart of the book. It centers around the idea that the knowledge we have when embarking on any journey is always incomplete, as in a rough draft, and can also be rough as in difficult. I liked how it seemed to encompass all the themes of the book. In an earlier version, the book was divided into three sections, but I ultimately decided on two because it felt right, I think in part because that felt connected to the binaries I see as being essential to the book: joy/tragedy, light/dark, old life/new life, sky/ground, internal/external, containment/space. Like two halves of one thing.

SPK: You use stanzas of two and three lines quite a lot. How are they particularly important or meaningful to you?

CP: That’s a great question. I think I did that more in these poems than I do in my more recent work on different themes. Many of them would start out not that way but when revising, that form often ended up feeling most fitting for the content. Philip Levine Prize judge Peter Everwine said my poems felt like breathing, inward containment, outward space, and I loved that. I think that does have to do with it — also, a lot of these poems center around the first years of a marriage, so I think groups of two lines felt like they worked, and the three lines feel like they represent the two of us and a third as the old self one is leaving at any moment, or the two people and the moment.

This is all post-analysis. At the time I guess it just felt right. I recently read an interview with Edward Hirsch about his book Gabriel and his use of tercets. He said one thing that drew him to it is that each stanza has a beginning, middle, and an end. I think that’s part of why it felt like it worked with the idea of leaving an old life and beginning a new one and with my narrative style.

SPK: What draws you to those French forms, the pantoums and the sestinas?

CP: In the very first workshop I took in 1996, the summer before my senior year of college, the teacher Donna Masini and my classmates started calling me Christine Sestina. She assigned one and it was the first time I’d written one. I remember I wrote it on a bus traveling back to NYC from Philadelphia the night before it was due and that surprised people. It was called “Keeping Still with Water” and was basically the story of the visit I had just come from. I liked how the repeated words helped me explore something different in each stanza but also kept things centered around that same moment. I’ve probably only written a total of five or so. Some of them don’t work. I think I was first assigned a pantoum when I was in grad school. The repetition of whole lines feels like it’s fitting for a darker subject, that feeling of being trapped a little bit. I haven’t been writing in those forms lately but I am glad to know they are there to try out when I might need them again.

SPK: Are there any poems you decided to leave out?

CP: Once I became clearer about the themes of the book, I was able to narrow things down a bit and take out poems that didn’t seem to fit in as well or were not as strong. Every year that I made slight revisions I took out a few poems and put in a few newer ones, so it was pretty much in flux. I think I took out about five poems in my final version.

SPK: What have you been reading lately?

CP: Most recently I've been reading Mark Wunderlich, Philip Gross, Imtiaz Dharker, Erin Belieu, and Beth Ann Fennelly. I find myself returning to re-read Dana Roeser, Sidney Wade and Edward Hirsch for momentum and renewal. I've been especially interested in other people's first books lately, and two I totally loved is Alison Prine's book Steel, which just came out, and fellow Anhinga Press poet Robin Beth Schaer's Shipbreaking. Also, The New World by Suzanne Gardinier.

SPK: What’s the next writing project for you?

CP: Well, New York City appears in my next manuscript in an even more historical lens, through the retelling of the experiences of my grandparents, Polish immigrants in the 1930s to the Lower East Side, where I grew up and my parents still live. While Rough Knowledge centers around the journeys of one speaker, my second manuscript examines multiple journeys. Poems involving my grandparents and drawing on New York City history, from visits to Ellis Island, the Tenement Museum, and my own childhood neighborhood as well as historical readings, make up one thread. The other two threads are those of the experiences of my adult English as a Second Language students in a new land and language and those of a child and mother learning their own new world. I am in the process of finishing up this manuscript. Some of my newest poems are informed by my son’s questions about everyday occurrences and wonders like machinery and space and balloons in the sky.

Christine Poreba is the winner of the 2014 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry. A native New Yorker, she currently writes and teaches English as a Second Language to adults with Leon County School’s Adult & Community Education program in Tallahassee, Florida, where she lives with her husband, young son, and dog.

Sean Patrick Kinneen is a Master of Fine Arts candidate in poetry at California State University, Fresno. He serves as an editorial assistant for The Normal School literary magazine and the Philip Levine Prize for Poetry.

Hood by Sohrab Homi Fracis

1981 was a bad year for a Parsi to come to America. The Iran hostage crisis had left Americans with a smoldering resentment of foreigners. “Go home!” Viraf was told.

Not to his South Bombay stomping grounds: Marine Drive, Churchgate, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Cuffe Parade, Eros, CCI, Colaba. Not to Seth Building and his loved ones: Mum, Dad, Mamaiji—best not to even think of Maya.

Read MoreCalifornia is Sinking by Martin Ott

California is Sinking by Martin Ott

It was water draining, earthquakes kissing in the shade of the moon winking in tune with the marionettes of Godzilla tap dancing for dinner. It was the office pool being rigged before the steering column in the ribs, the storage shed turned into a homeless brig, the matador’s cape or baby’s bib hung in the closet or on a billboard begging for consideration, the fib that became the real story rehashed until time lost its will. It was the small screen sucking us in, the vodka gimlet transformed into gin, the famed taco truck up in smoke that we followed for years, the treasure in limbo just beyond the beyond, the yolk discarded in the heart-smart omelet. It was the drone sent out for cigarettes by the director lost in the desert. It was the lost scene in Steinbeck’s last work. It was the invisible collapse of the land’s face, stretched taut like an actor turned professional patient. It was the hidden reservoir beneath the migrants streaming into the void. It was the crash that no one heard and the warnings we pretended to ignore.

Martin Ott is the author of six books of poetry and fiction, including the poetry book Underdays, Sandeen Prize Winner, University of Notre Dame Press and the short story collection Interrogations, Fomite Press. More at www.martinottwriter.com.

All We Know by Latifa Ayad

My father gave me my mother’s last name. Kirsch. A good, white-sounding name. I inherited nothing from him. I have gray eyes, light brown hair, skin that burns easily on trips to the gulf. They named me Chi, for the Cochiti pueblo, where my parents first met as part of a tour group. They didn’t name me Zara, my grandmother’s name. Zara was supposed to be an apology, because he missed his mother’s funeral, and because he was never going back to Libya, not after he tasted freedom, the sweat that beaded on my mother’s upper lip in New Mexico, and the fry bread they served at the pueblo, hot, drizzled in honey.

Read More