Searching Childhood: Driftwood Center in Daylight

You know bad things can still happen in the bright of sunshine: the man parked in that in-between place at the back of the Center and the back of the strip mall on the other side—you, a whisper of a girl at age 7, already old enough to know he was watching your every move long before he called you over to his car. That was the year little girls went missing on the news, unwatched by mother eyes but net-caught in a man’s sight. He called you, said he had a present for you; he was out of the car and walking your way, every step closer a drumbeat against pavement, a danger-singing bloodrush—you ghostgirl and disappear to safety like you were trained.

This was the place where you solidified your cinderblock Cinderella status, playing with the other junkyard kids, getting into trouble, breaking into storage units, digging through boxes for something none of you could name yet, looking at adult magazines, playing a game called “mattress surfing” where you climbed up high on a bunch of stacked mattresses and then slid down before you were caught and chased off. This is the place where you played in your small plastic pool alone—the pool just behind the unit and under the kitchen window so your teenage sister could make sure you were still there from time to time. How easy it was to misplace a girl even in daylight.

Searching Childhood: 1978 Station Wagon

This is not a place you can pinpoint on a map: four tires, silver trim rusted to rundown, the first used car that made you feel like a normal family—a station wagon already close to 20 years old and running on quick fixes, a soon to be home for a mother, three daughters, and two dogs. You’re eleven years old, a girl older than her years, harder than she should be. There is nothing normal about your family.

The night before the eviction, you were left behind by your mother and older sisters as they took as much as they could to the storage unit—your usual seat in the car filled with boxes and trash bags.

The night before the eviction, you were afraid to be alone. The duplex had a backdoor with no doorknob, only an open-to-the-night hole. You sat on the floor watching the backdoor, that hole of darkness never leaving your sight, even when you imagined a man’s fingers snaking through it.

The night before the eviction, you stared down that black circle in cut wood until you heard the growl and gurgle of the station wagon returning.

Living in the car wasn’t the first choice. Your mother bounced checks to buy camping gear: a tent, tarp, sleeping bags, things to start a fire. The campgrounds lasted a few weeks, another survival test. You didn’t know it was possible to get an eviction notice from a campground until your mother couldn’t pay the daily fee.

The free campground after that was nothing more than a field surrounded by woods on all sides—a field full of men in tents, men in RVs, men in cars, men gathering around our fire with sunset dinner glances, men outside our tent with night-hungry tongues.

The car had locks on the doors, a metal frame of safety from the men looking to disappear girls, to bury them beyond the tree line in woods you already knew better than to explore.

“You can’t park here.” Loitering is only a problem if you are a certain type of person.

“You can’t park here.” During the day, we learn where we are allowed to be: inside the library, at the beach, riverside park.

“You can’t park here.” At night, we learn where we are not allowed to be: Walmart parking lots, library parking lots, parks, the beach, in neighborhoods, rest areas off the highway for more than a few hours. “You can’t stay here overnight” is another way to say, “You can’t park here, you can’t exist here or anywhere.”

You go through one of the many insomnia periods of your life. Sleeping sitting up in the backseat with your sister—both of you fighting for space—makes sleep as impossible as when the breath of men fogged your tent.

If you slip into sleep, there are random wakeup calls—bright bulb flashlights, a tapping on window glass, a startle-flurry as you wake to lights, men’s hands, a deep voice. Some nights it’s a security guard, other times the police. Every few hours, your mother moves the car to a new parking lot, a new not-welcome-here spot for a few hours of sleep before being told to move again.

Men have disrupted your sleep since you were born into this world—your father drunk-crawling into your little girl bed, your father (gas can in hand) threatening to burn the house down while his family of women slept, the watchers, the deep voices in shadows, the man outside every window.

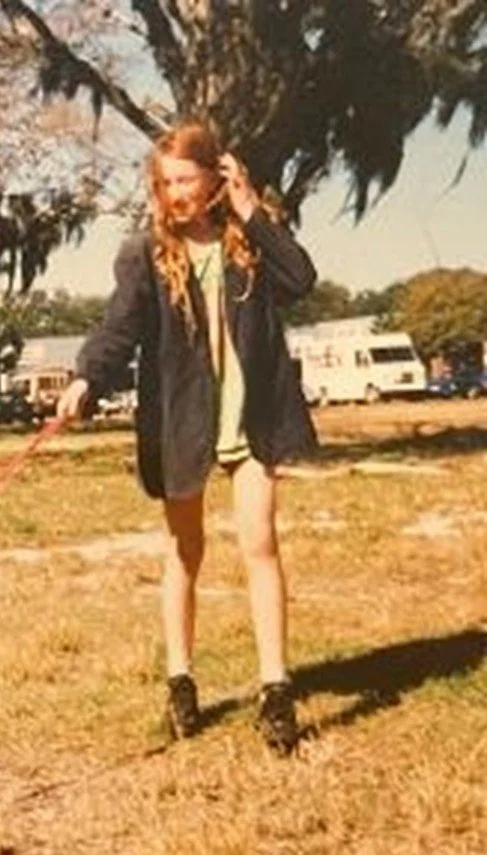

You turn twelve, a girlwoman of wild red hair, rage and rags, still unloved and living in a station wagon and the only thing you want—just one night of safe sleep.

Maggie Wolff is a poet, essayist, and Ph.D. student in English Studies. She recently won an AWP Intro Journal Award for her poetry, and her work has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Juked, New Delta Review, and other publications. She is the author of a chapbook, Haunted Daughters (Press 254).