Samina Najmi’s debut memoir, Sing Me a Circle is a deep reflection of the author’s origins, experiences, and haunting moments that have shaped her identity. Through love and loss, these essays show us how the idea of home evolves through time and memory.

In an interview, we discuss the writing process with Samina Najmi and how the themes and powerful moments in Sing Me A Circle reveal to us about ancestry and how our origins mold us as individuals.

Isabella De La Torre: Firstly, I wanted to start off by asking you about your experience working with Trio House. What was the process like? How does it feel to have your first book out in the world?

Samina Najmi: I'm honored and delighted to be in conversation with you, Isabella. Working with Trio House Press has been a positive experience. They’re a small independent press based in Minneapolis, publishing mostly poetry since 2012. I hadn’t heard of them until I saw their call for manuscripts for the 2024 Aurora Polaris Award in an issue of Poets & Writers, and circled it. Then our own Mai Der Vang included the call on her LitOpps list, so I did further research on the press. I liked their mission, took a deep breath, and submitted my manuscript to them. As you know, it won the contest. Sing Me a Circle is only their second Aurora Polaris winner, so we’ve grown together in the process. I’m impressed how fast they moved to publication. I began writing my memoir-in-essays in 2011, so it had a long gestation period, but once it got to Trio House, the book was birthed in exactly nine months. That’s seven months before the official October 1 publication date!

How does it feel? Still pretty surreal. I have coedited collections of scholarly essays before, but there’s something about my life-writings being gathered and shaped into a book that feels truly a first. It’s been thrilling, humbling, and occasionally unsettling to let the world in like that. But mostly, I’ve been feeling very moved by the love, especially in Fresno.

Isabella De La Torre: I also wanted to ask more about the structure of your book. What connections did you find between each essay as you began to compile this book? The essays seem to build on each other, with each one informing and reflecting on the other (a circle!). Was the process difficult?

Samina Najmi: Thanks for seeing that relationship among the essays. Such a great question. I think the fact that I wrote these essays over a period of ten years has a lot to do with the structure. There’s a zooming out that has to happen so you can see the whole in any book you’re putting together, but for me it also meant looking at the events and preoccupations of the essays as they emerged over time. On some level, they were so disparate—far-flung settings, people and places long gone, and present situations that seemed to have nothing to do with them. But ultimately, they’re all held together by a single consciousness, so I began to see the patterns. I wouldn’t claim that the process was easy, but in looking at the essays together, which also meant looking back through time, I was surprised how consistent that consciousness had remained. Perhaps we obsess about the same few things in life—in my case, family and home and the mystery of time—just in different contexts, and from varying perspectives? I decided to divide my essays into three very loosely chronological sections, maybe because that bit of contouring gave the book greater definition. But you’re absolutely right that the essays inform and reflect on one another, so you could read them in any order.

Isabella De La Torre: Speaking of relationships and crafting, do you have any specific writing rituals or ways to get your thoughts organized before writing? What techniques do you use before working on essays or larger works?

Samina Najmi: I wish I could say I write every day, but that’s a practice I have yet to cultivate. When I feel an essay coming on—usually when I’m preoccupied with a thought or feeling—I set my alarm for 4 am the next morning. That’s my golden hour for generative writing. If I write with full-on focus for 2-3 hours, it’s a very good writing day. I might tinker later, but the wee hours are the single most important writing ritual for me. For the past nine or so years, my navy-blue armchair in the living room has served as my writing station. I used to sleep in it while I was pregnant with Maya and Cyrus long years ago, but it now inspires other kinds of creativity.

Isabella De La Torre: Diving deeper into the themes of the book, I noticed that the collection deals with the themes of place and home, detailing how keeping our families and stories close to us keeps us grounded in our identities. To you, what is the importance of remembering these stories?

Samina Najmi: Teaching American Indian Literature every so often, especially as a writer of creative nonfiction, has taught me so much about the interconnections of history, memory, identity, and story. I think often of a line from Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday’s family memoir, The Names: “If I were to remember other things, I should be someone else.” They say memory is selective; what we do and don’t remember matters because memory shapes our identities and our stories. You might also say our families are our stories. They give us context, an origin story, and a sense of place, but also a frame of reference for our future trajectories. Our lives are relational—as Cree scholar Shawn Wilson illuminates so eloquently in Research as Ceremony—and family may be the most significant of those relations, one way or another. How do we tell our own stories, to ourselves and others, without them?

Isabella De La Torre: I like how you mentioned that our families become our stories. I also saw that reflected through the various locations presented in the essays. There are several countries mentioned in these collections of essays, including: The United States, Pakistan, and England. You articulate your experience with the intersection of these various cultures. You use the circle as a metaphor for our internal journeys, as we often retrace the steps of our own past and the past of the generations before us. Why do you think the act of retracing is necessary for us to come to terms with our identities?

Samina Najmi: A life lived on the intersections of nations, cultures, faiths, and languages can be hard. As a child, I wanted only to belong, but no fit was exactly right. In time, though, I began to value my outsider-insider status because I realized it afforded me a richer perspective. Often it meant I could serve as a bridge. Empathy for others is a little easier to come by if your own experiences have been marked by hybridity.

As to the necessity of retracing our journeys, I think the act of revisiting and retelling our stories grounds us in self-knowledge. The past is often painful terrain to go over, but individuals in each generation have to make sense of that inheritance for themselves—to acknowledge it, reckon with it, choose what to keep and what to leave behind—in order to know who they are and where they’re going. That’s how time layers our stories. As I grow older, I value more and more the perception of time and experience as circular. Again, contemporary American Indian literature demonstrates this in all genres; think Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, Louise Erdrich, and the queer feminist theorist Paula Gunn Allen in the 1980s, but also more recent writers like Mona Susan Power and Tommy Orange, among others. None of them treats time as linear. Because it’s circular and layered, like memory and grief and thought itself.

Isabella De La Torre: I also thought that “The Cat Connection” was such a touching tribute to the various cats that have come into your life. I saw that often in the essay, the animals and humans in the piece seem to reflect each other when it comes to addressing fear. Why did you want to tell the story of these special felines and discuss these themes?

Samina Najmi: You know, no one has asked me that question before! It makes sense that it comes from someone who centers animals in her own life. I didn’t grow up with pets. Animals in poorer countries usually have to make it on their own. But the story of my relationship with cats, in particular, is complicated, as you know from “The Cat Connection.” I grew up with nightmares about them, and I have no idea why. (To go back to your earlier point: If there’s a story there, it’s lost to me without the memory.) Winnie and Snickers, the cats we adopted a dozen or so years ago, have slowly intervened in my phobia. I’m still not comfortable holding them, though I love and care for them. But here’s the thing: I have always wished for a fuller relationship with animals. Even as a child, I didn’t want to eat them as beef or chicken. The first cat I knew was my husband’s yard cat MoeMoe in Massachusetts, and I loved taking photos of the two of them together. It was the closest I could get to having a relationship like that. After MoeMoe died, our grief made us both vegetarian because the cognitive dissonance of grieving for one animal and eating another was hard to stomach.

I didn’t set out to write about cats, but their stories are so bound up with mine that inevitably they popped up in places. Stories of fear, but also of place and habit, and learning to anchor oneself in the moment. While Muslim cultures tend to elevate cats, most Indigenous oral traditions and creation stories—look at me circling back to our course!—simply don’t endorse hierarchies between human and animal, to begin with. We have much to learn from animals if we can get our egos out of the way long enough to observe them respectfully. (Shoutout to Fresno writer Talia Kolluri, whose short stories do just that.) My relationship with Winnie and Snickers has acquired more depth and dimension since the fire in my home. And as I write, Winnie, now a venerable thirteen years old, is beginning a new life in Houston with Cyrus. My first essay of the year is prompted by Winnie’s migration.

Isabella De La Torre: I loved seeing that blossoming relationship between you and your cats. I hope to read more about them! After this publication, are you looking to try something new with your writing? What direction do you believe that you are heading in?

Samina Najmi: Yes to something new! I’m still working within the genre of the personal essay—it’s such an expansive genre—but the next collection is likely to be less sprawling in time and space. I’m working on a narrower canvas, a period of time some years ago when fire, breast cancer, and empty nest coincided with the pandemic. I’m sure these themes won’t remain bounded, but will find connection to other themes. After all, everything’s connected.

I’m also keen to learn more about the craft of poetry. Some readers have commented on Sing Me a Circle as a hybrid book, a memoir-in-essays incorporating poetry. As a literary critic, I know that sometimes readers illuminate things in an author’s writing that may have eluded the author. So, I’m curious to explore the lines between prose and poetry, particularly since some of my recent essays have been condensing to flash. I see the value of genre containers, but sometimes our writing spills out of them. I figure I must get out of my own way in order for my writing to grow.

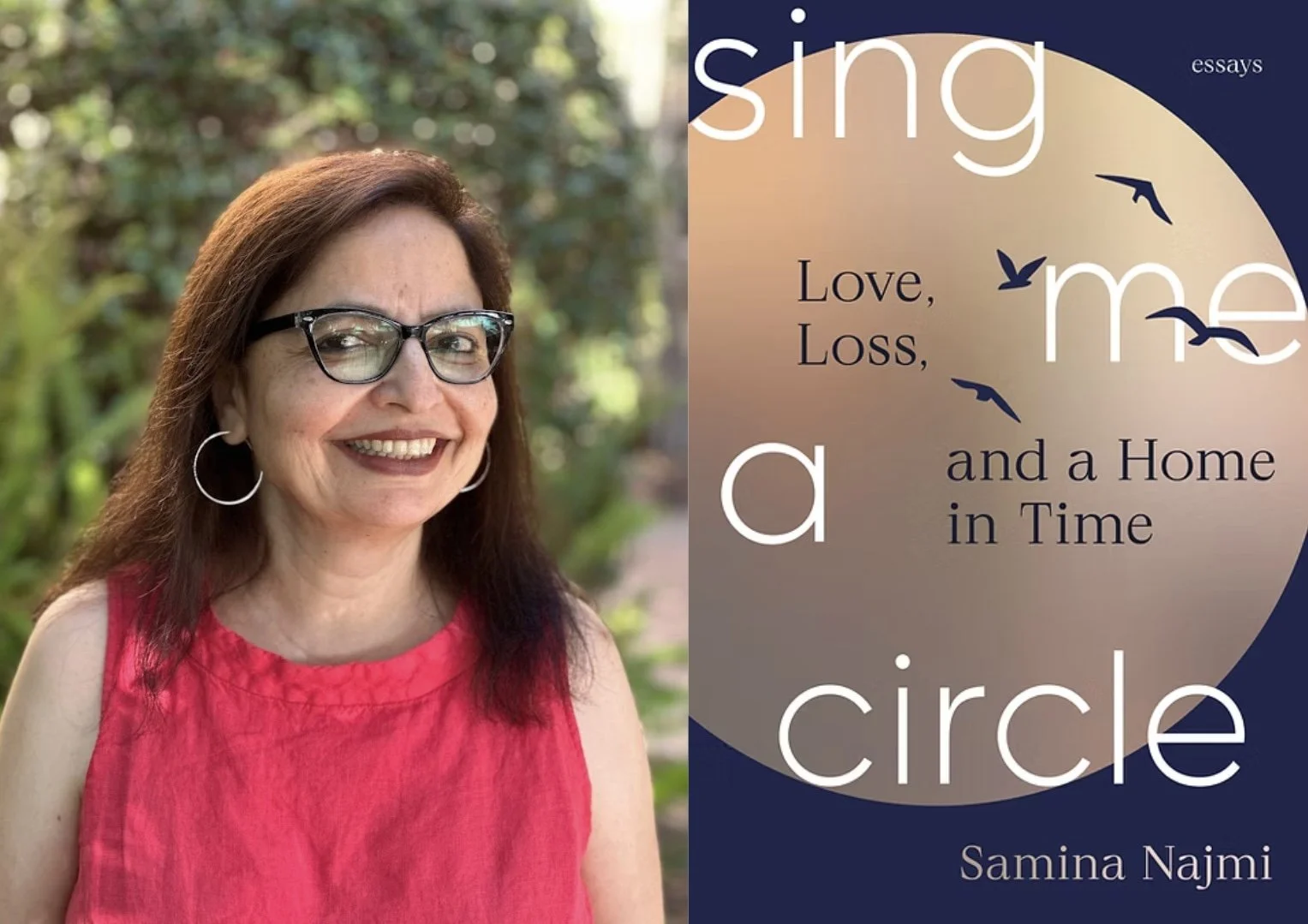

Samina Najmi teaches multiethnic US literature at California State University, Fresno. Her memoir-in-essays, Sing Me a Circle: Love, Loss, and a Home in Time, won the Aurora Polaris Award in Creative Nonfiction and was published by Trio House Press in Oct, 2025. It has received a starred review from Publishers Weekly and is featured among Poets & Writers’ five nonfiction debuts of the year. It is also included in the Best of 2025 roundups by Debutiful and the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP). Samina’s essays have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and have won other honors. Daughter of multiple migrations, Samina grew up in Pakistan and England, and has lived in Fresno since 2006. Twenty-five years after obtaining her doctorate, Samina has enrolled in Fresno State’s MFA program in creative nonfiction, and this is keeping her humble.

Isabella De La Torre is a second-year MFA creative writing student studying poetry. In the future, she hopes to be a college professor and get her PhD in English literature. Her poetry has been published in Honeyguide Literary Magazine, the Behemoth Biennial, and others.